Now is the time to visit Cambridge if you’re a fan of concrete poetry. At Kettle’s Yard is Beauty and Revolution, an exhibition of work by Ian Hamilton Finlay, while the Centre of Latin American Studies plays host to a group exhibition entitled A Token of Concrete Affection. Both are furnished from the private collection of life-time scholar and internationally renowned concrete poetry expert, Stephen Bann. Both provide rare opportunities to see poem-objects, memorabilia, and personal correspondence not usually available for public viewing. And both are the subject of a day-long symposium, Concrete Poetry – International Exchanges. The symposium will be hosted by the University of Cambridge on 14th February; here are some of the thoughts I will be taking with me on the day…

Ideograms have a lot to answer for in the evolution of twentieth and twenty-first century poetics. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, poets such as Ezra Pound were beginning to import into their poetry what they conceived of as the principles of Chinese ideograms. An ideogram is defined as “a written idea” or “a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language and specific words or phrases”. This application of ideogrammatic structure in European and American poetry gave rise to the early twentieth century avant-garde movement know as Imagism. Imagism might most simply be described as the production of a simile where a line break or punctuated pause (e.g. semi-colon) takes the place of the like/as, or where the spatial proximity of phrases is used to imply relation and preclude the need to state explicitly that x “is” y (as in the structure of metaphor). In a Station of the Metro, Ezra Pound’s two-line poem from 1913, is an example of Imagist poetics at work:

The apparition of these faces in the crowd;

Petals on a wet, black bough.

Here, the spatial organisation of words has a significant part to play in the structure and generation of meaning in language. The understanding that this spatial organisation might actually be regarded as an integral component of the meaning-making properties of language is the point at which Imagism tips over into concrete poetry. Where Ezra Pound implies the similarities between “faces in the crowd” and “Petals on a wet, black bough”, the concrete poet might caption a photograph of faces in the crowd with Pound’s phrase “Petals on a wet, black bough”. Concrete poetry collapses difference and extends the literal. It doesn’t just invoke or imagine new realities; it creates them. By insisting on its tangibility, concrete poetry transforms literature into art.

Concrete poetry is draftsmanship; sculpture; architecture…

This is the space that Ian Hamilton Finlay’s oeuvre occupies. Beauty and Revolution divides the work into five themes: concrete and kinetic, boats and signs, emblems and medallions, Little Sparta, and revolution. My own feeling is that these categories are somewhat artificially imposed upon the items on show. The real reason for the exhibition – as explored in Bann’s accompanying catalogue essay – seems to lie in Finlay’s relationships with Stephen Bann, the curator and collector, and Jim Ede, who created Kettle’s Yard. I would have liked these human connections to have been made more concrete in the exhibition itself.

Finlay rebels against and reinvents standard modes of language-making in a series of materially-engaged, aesthetic acts of revolt.

The exhibition’s title, Beauty and Revolution, arises out of Finlay’s commitment to a kind of aesthetic activism. His life’s work is an extended exploration of the relationship between how something is done, or made, and what that making does and/or says. As an artist, he is explicitly aware of the relationship between form and function and relentless in his commentary and critique of the discrepancies that arise between the two. Finlay’s work reflects upon and interrogates its modes of production and presentation; it rebels against and reinvents standard modes of language-making in a series of materially-engaged, aesthetic acts of revolt.

For Finlay, language is an agent of change. This is explored with a force that borders on violence in works such as Marat Assassiné (1986), The Revolution is Frozen (1990), both with Gary Hincks, and the fractured stone inscriptions that litter Little Sparta. I’m normally more drawn to Finlay’s book work but this exhibition features more prints and photographs than pages. A Rock Rose (1971) with Richard Demarco, exemplifies a quieter form of violence while linking more explicitly to Finlay’s work with words. Are the ship’s sails rose petals blooming from the rock? Or is it the rock below the boat that forms the flower – a flower that rises to wreck the boat as it blooms?

This tension between beauty and violence is extended by Finlay’s preoccupation with war. Time and again he inserts the images and icons of war into ‘natural’ contexts, and vice versa. But why? There must certainly have been a battle against both weather and moorland in order to maintain the garden at Stonypath, but there is a struggle to articulate more than that. I overheard one visitor in the exhibition suggesting that this work reminds us of the violence inherent within nature, but does this need to be taken a step further? Rather than understanding these stone warships, half-hidden under leaves in Little Sparta, as elements of surprise, imposed somewhat awkwardly upon the idyll of rural Arcadia, perhaps the comment being made is that these tanks and battleships were always already there? That in fact they evolved out of the beating heart of this Arcadia, the most recent descendents of beetles and birds? Perhaps Finlay is declaring that Eden was already at war? Camouflage is part and parcel of evolution, after all.

Over at the Centre of Latin American Studies, A Token of Concrete Affection is more text-focused than Beauty and Revolution. Both exhibitions draw out the positive political implications of concrete poetry’s insistence on language-formation as a form of activism. But the Centre of Latin American Studies is a working academic space, and the effect is more open archive than exhibition. Although the exhibition spreads over two floors, the rooms themselves are relatively small and the work would benefit from having slightly more room to breathe.

Nonetheless, the relationship between words and revolution here is, once again, strong. The concrete poetry manifesto was alive and well in Brazil during the 1960s and ‘70s. The exhibition’s accompanying essay highlights the continuity between linguistic activism and the social implications of these aesthetics. We’re introduced to the Jornal do Brasil, whose motto – “attempt to innovate the traditional methods of the press” – was part of a sociological as well as a typological revolution. Founded in 1891 and still going today, the Jornal contained revolutionary coverage of music, cinema and Carnaval, as well as “the first regular international politics section”, “the first women’s section” and “the Open Society editorial initiative [in 2006], which enables any citizen to send their text to be published in a relevant subject section within its printed pages”.

If revolution is an act of transformation, the risk that concrete poetry runs is of being caught in between, of being not-quite-both – half-man, half-beast…

Perhaps inadvertently, A Token of Concrete Affection challenges the definition of the ideogram as “a graphic symbol that represents an idea or concept, independent of any particular language”. Graphically, you can get much from this work even if you do only speak English. Augusto de Campos’ italic spiral translation of William Blake’s The Sick Rose (A Rosa Duente) is beautiful no matter what language you speak. But even though some words are helpfully provided in both English and Portuguese, and almost all the correspondence is in English, the experience remains problematic.

The sense that concrete poetry communicates independently of any particular language, that the concrete poet, in combining the graphic and the literate properties of language, somehow transcends both, is revealed to be a myth. It is the age-old problem of interdisciplinarity: you think that by combining languages you expand your audience but in fact you end up reducing it. And it is for this reason that concrete poetry does not appeal to nearly as many people as it should. If revolution is an act of transformation, the risk that concrete poetry runs is of being caught in between, of being not-quite-both – half-man, half-beast – sometimes beautiful, sometimes frightening, but almost always challenging.

Beauty and Revolution: The Poetry and Art of Ian Hamilton Finlay is at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge until 1st March 2015.

A Token of Concrete Affection is at Centre of Latin American Studies, Cambridge until 27th February 2015.

Image credits (top to bottom):

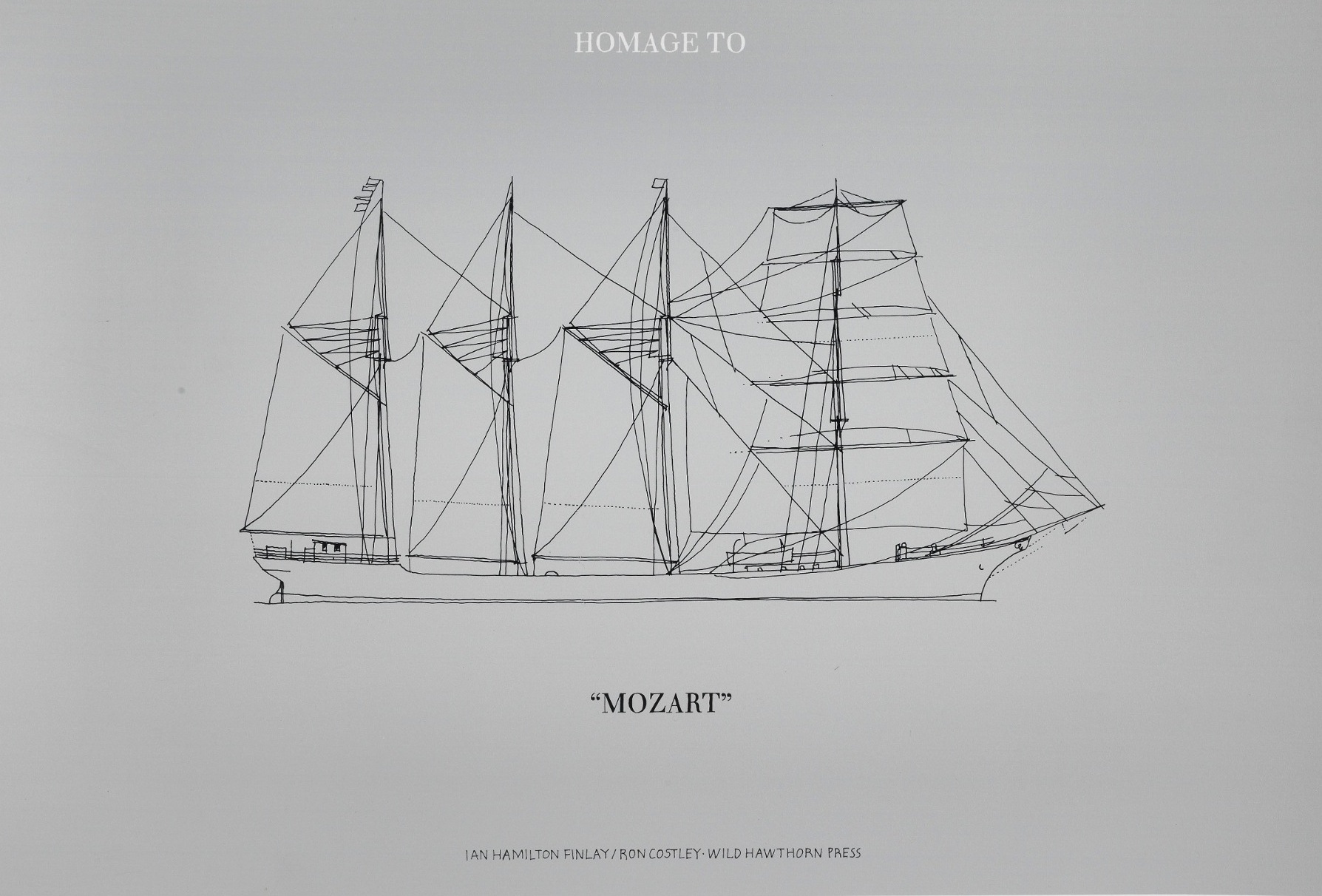

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Homage to Mozart [collaboration with Ron Costley], 1970

Ian Hamilton Finlay, After Piranesi (1), 1991 with Gary Hincks

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Spiral Binding, 1972 with Ron Costley

Ian Hamilton Finlay, Wildflower vase

Ian Hamilton Finlay, A Rock Rose [collaboration with Richard Demarco], 1971

All by courtesy of the estate of Ian Hamilton Finlay