There are many different approaches to drawing animals. In particular there was a shift in the 19th century away from French idealism towards an approach, led by British artists such as Edward Lear, that prioritised drawing direct from nature. The work of Amy Dover, a fine artist and illustrator based in Newcastle, England, draws upon some of these histories and blends realistic life drawing with memory and imagination.

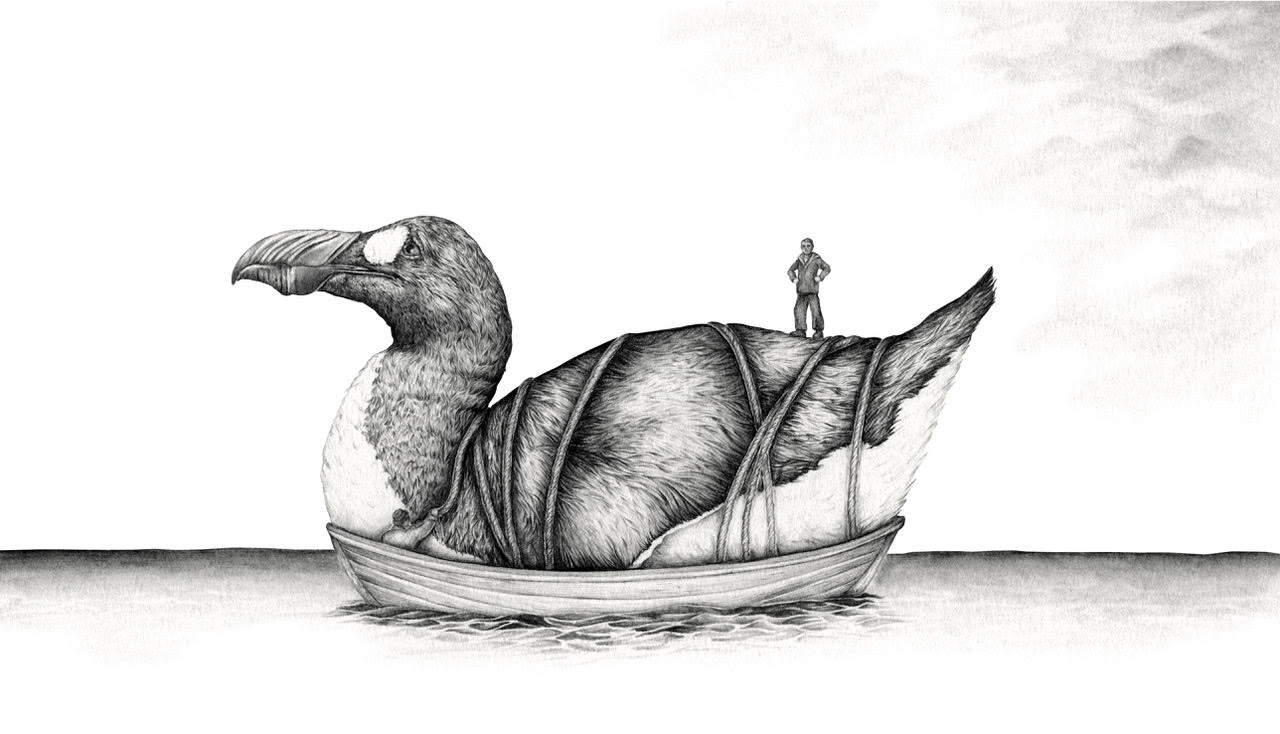

Dover has recently been working on an ongoing project entitled Endlings, which takes as its subject of focus animals that are under threat of extinction. For her MFA exhibition at Edinburgh College of Art, Dover showed alongside her distinctive drawings a text installation that included all of the animals on the IUCN red list of threatened species. The installation included not only the animals’ Latin names but their common descriptions too. This brutally systematic list of names was a haunting accompaniment to Dover’s drawings, which are always so full of character and life.

What drew you to the subject of “endlings”? Why does it feel important to you?

Drawing animals has been central to my practice for some time now, I am a little obsessed with drawing feathers and fur. A few years ago it dawned on me that many of the animals I was choosing to draw – bears, wolves, hares and others – were extinct or endangered from the British Isles. I fell down the dark rabbit hole or learning about extinction and the Anthropocene. I also used to draw from mythology and literature and I discovered that the true stories of animals were often even more bizarre. In order to highlight the need for conservation in the face of the sixth mass extinction I chose to tell the strange stories of individual animals and how the last of the species disappeared.

Some of your works feel very realistic; others are more fantastical or surreal. Could you say a little about these different approaches in your work – how you navigate between them or sometimes blur them together?

In the book Darwin Becomes Art, Hugh Ridley talks about the influence of science on drawing from life. I don’t feel I can do the animals justice unless a study them. Some of the animals I have drawn, I have met. I travelled to Thailand earlier this year to meet and draw rescued animals and tell their story. I bring a little anthropomorphism (a dirty word in science, I know) to help with the narrative. I like to toy with allegory and surreal proportions but keep the animals realistic to ground the realism of the story.

Could you say a little about the text piece in the MFA show of all the animals on the IUCN red list? Why did it feel important to make the list “real” in the gallery?

It’s a shockingly long list isn’t it, and that’s just the animals. The drawings depict, and name individual stories. But there are many crickets, snails, nameless fish and tiny frogs which don’t get the publicity like the lions and tigers of this world. So I wanted to show all the species equally. Human speciesism – believing that we are more important than other species – is responsible for a great deal of damage. The list uses scientific names, but I didn’t feel that would have as big an impact. So I translated all 13,000 in to the common names. Some have specific names like the “bastard sturgeon” and others haven’t been named so are just a land snail. It was a huge task, and only highlighted how many animals are disappearing. It was a great talking point at the exhibition and people spent a long time looking at it.

You’ve previously exhibited your sketchbooks alongside completed works and it provides such a great insight into your working process. Could you say a little about how you work, the combination of images and thoughts, and then how you decide to work up specific ideas into more finished works?

Thank you. The sketchbooks are my research but become artefacts and pieces on their own (hopefully). Sometimes the sketches evolve further in to final pieces. I adore the sketchbooks of explorers and naturalists. As they travelled documenting and drawing animals newly discovered, I am drawing and documenting those animals which are disappearing. One of the sketchbooks is from a research trip, to a rescue centre in rural Thailand. There were a whole range of species that have been harmed by humans, rescued out of captivity or from the international pet trade. There were many species not native to Thailand including a huge cassowary called Bernie, who was somehow smuggled out of Australia. I spent one afternoon with the two orang-utans, drawing them playing and trying to steal my shoes. The sketch books are not only a journal but a way to explore ideas. Drawing and notes helps me develop concepts and understand things more greatly.

You work as both a fine artist and an illustrator. How do the two differ for you, or is it not really a significant distinction?

This is a question I ask myself. I have always sat in a hazy area, but I don’t think it needs to be defined. My main practice used to be exhibitions, but I stared to take on a lot more commissions. I do commercial work for clients like Redbull, M&S, World Animal Protection, Target and others: this I would class as illustration. But who knows? I just like exploring concepts through drawing, and if I can help with conservation at the same time it can’t be bad.

Follow Amy Dover on Instagram.

www.amydover.com

All images: Amy Dover.

This is part of ROOT MAPPING, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring which maps might help us live with a clear sense of where we are. ROOT MAPPING is conceived and edited by Melanie Viets.