Sensory-visual notes across three greenhouse rooms at Brooklyn’s Botanical Gardens

This past August in Berlin, I joined 10 other Perennial Institute participants for an all-day excursion to the Berlin-Dahlem Botanical Gardens as part of a week-long programme together exploring creativity through the lens of plants. After touring the garden’s extensive greenhouses, the artist Shota Nakamura introduced our afternoon drawing assignment. We would all take solitary walks anywhere on the garden grounds for about 30 minutes, and then draw a map of our travels from memory.

Like hot air rising, I started at the ground floor greenhouse desert rooms and gradually ascended to a long second floor clerestory room with a glass pitched roof and a continuous line of open, low-lying windows. They let in wisps of cross-breeze through the veil of plants to either side of the room’s central walkway.

Many individual plants made impressions on me along my walk (as was the case all throughout the day) but when it came time to draw, I found myself returning instead to the overall shifts in temperature and atmosphere, especially transitioning between rooms.

The Berlin-Dahlem Botanical Garden’s 16 climate-themed greenhouses — 14 of which are connected to each other — make it possible to walk relatively seamlessly around the world’s various climate zones. This experience suggested an alternate take on Lars Lerup’s writings on “the continuous city”. Rather than envisioning our world as one spherical city towards an inevitable embrace of total urbanization, the greenhouses rendered the globe as a collaboration between nature and humans in the form of one continuous garden.

Perhaps ironically though, my walking resembled that of an urban Situationist. This time I made decisions on where to walk based on signs of coolness, choosing to move towards succulent greens, silvery reflective leaves or crisp patches of distant trees through open windows. These more abstract sensations, I quickly realized, evaded my attempts to commit them to paper later. Although I had been drawn to taking pictures of the building’s mechanics along the way – traditional column radiators, electric fans, garden hoses and exposed plumbing were all familiar conductors of climate – I wondered, what do air, temperature, moisture, scent and sound look like?

The challenge of conveying (and recreating) climate reminded me of abstract temperature diagrams by the architect Philippe Rahm whose architectural practice is grounded first and foremost in designing climates, rather than manipulating conventional building materials.

In a review of Rahm’s Jade Eco Park in Metropolis magazine, the editor Avinash Rajagopal cited a Harvard lecture at which Rahm spoke where the dean Mohsen Mostafavi admitted “he couldn’t see the totality of a park in the design”. Coming to Rahm’s defense in his article, Rajagopal described Rahm as a designer of “invisible architecture”, adding that “the things that can be seen — the trees and the devices — are merely structural elements. The edifice is the multisensory experience.”

Something similar might be said of botanical greenhouses. When observing visitors ranging from Sunday couples to buzzing groups of school children, it’s clear how sensory of an experience the gardens are first and foremost. But when left to our own devices and senses — especially urbanites — what framework do we have for looking for how climate is created and tended to in a garden setting?

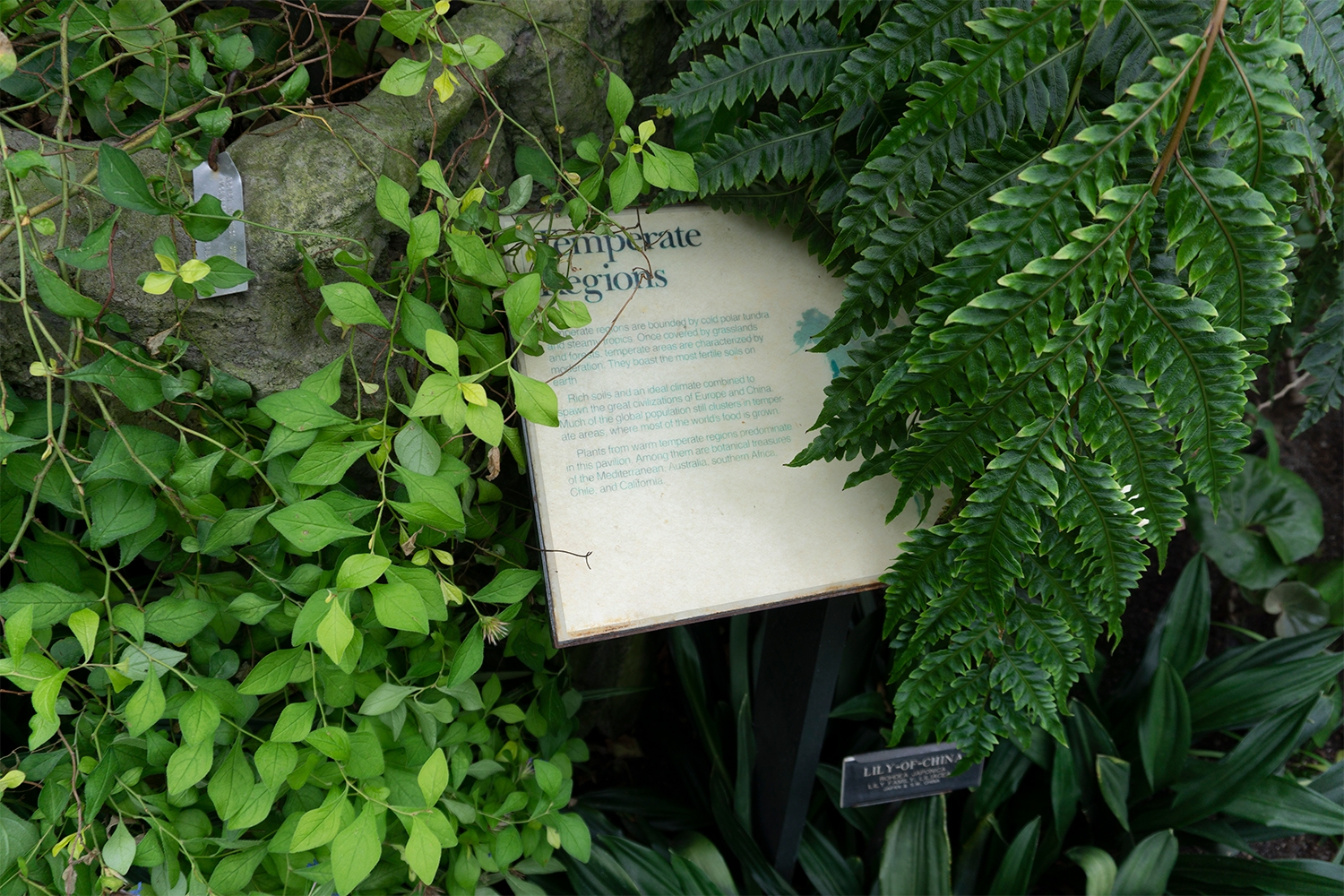

Despite attempts to label plant specimens with all variants of a plants name and to embed key thematic informational plaques, there’s a bit of guesswork for the unguided visitor. A dense planting of plants and labels can make it difficult to sort out who’s who. Nature still takes over in the garden exhibit, weathering informational labels and hiding them in the overgrowth.

With this in mind, I returned home to New York, eager to reattempt my botanical mapping assignment, but this time with my camera focused on how one might see the variety of qualities climate can take on.

The following passages highlight photographs taken over the course of two visits, one afternoon and the other early morning, observing climate in three greenhouse rooms: the dry and wet spells of the Desert Room, the suspended, imbued humidity of the Aquatic Room, and the animated effects of water inside the Tropical Room.

The Desert Room

My first visit to the Desert Room was in mid-to-late afternoon. The grounds were fully dry and you could hear the quiet crunch of gravel speckled under your feet — remnants from the main plant beds. No matter the decibels of visitors, whether lazy weekend strollers or swarms of school groups, the plants in the room maintained a quiet, restful and patient tone, in a state of surrendered anticipation for the bewitching watering hour. Two days later in the early morning, the atmosphere was still quiet, but the light was visibly brighter and cooler. The room’s faucet/watering hole had been turned on and a streaked path had been drawn in places from a dripping watering can or garden hose. The selective plants which had been watered were in bloom. The garden had the look of rocks suddenly glazed in color from getting wet. In areas that had been left dry, one of the ruby fruits of a tulip cactus lay fallen, shrunken and slightly charred on the ground.

The Aquatic Room

The Aquatic Room embodies a different version of stillness than that found in the Desert Room. A fog of humidity hangs suspended in the air and clings to all surfaces like steam from a shower. All things feel imbued with water, especially the hanging roots (shaped like calloused stalactites) who in fact thrive on nutrients absorbed from the dampened air. Water in the form of moisture is omnipresent and its movements take the form of a gentle pulse that fades in and out like a Cheshire cat across areas of the room over time. A puddle from one corner seems to reappear again elsewhere taking the shape of a soaked blossom. The mirror-finish surface of the bog water also flickers at random. Gentle ripples emanate almost imperceptibly from those tiny needle prick epicenters. At first glance, one might think it’s a falling drop of condensation from hanging roots or piping from the ceiling. But looking stealthily closer and for longer, the ripples actual come from tiny gas bubbles rising to the surface, caused by the rich soup of the bog’s decomposing organic material.

The Tropical Room

Upon entering the Tropical Room, there’s a cascade of trickling water, diffused by pendant branches overhead. You’re met with warm circulating air and strong perfume. It’s an animated place, like a working kitchen. Varying heights of canopy move water from leaf to leaf, resembling the mechanism of a Rube Goldberg machine, before absorbing into the ground or collecting in reservoirs of water. The effects of traveling water play a role in the metamorphosis of surfaces, including wetted leaves and colorfully streak-stained bark.

Across all three climate rooms, I was pleasantly surprised to find that plants indoors could still lead a semblance of outdoor living — after all, the aim of greenhouses is to recreate optimal outdoor conditions for plants indoors. However, perhaps what was so surprising was that despite being a sort of heaven and haven for plants, as well as such a photogenic attraction, the greenhouses were a place plants were tended while still rightfully being allowed to weather — dried from heat or stained from water.

That said, the close reading of signs of climate through plants made me more inquisitive about plant care instructions. Plants are often introduced to us in terms of their optimal and/or native climate and how much sun and water are needed for their survival. But these diagrams remind me once more of my dilemma conveying abstract sensations of the climate in the Berlin-Dahlem Botanical Gardens. What’s more, images of interior plants or plant care workshops often portray the picturesque — pristine-looking specimens or new cutting being repotted that feel in a sense brand new.

What if, instead, more illustrations of plants showed the effects of too much or too little of certain elements? Whether trying to understand how plants work in one’s one-family suburban home in a warm temperate region, or, of an apartment on the 30th floor of a glass high-rise, what might be said still of understanding plants not just as ideals of beauty, but canaries in a coalmine of the climates we find and make in the world?

All image credits: Maria Kozanecka.

This is part of The Learned Pig’s Tuin Stemmen (Garden Voices) editorial season, autumn-winter 2018/19. Guest editor: Marloe Mens.