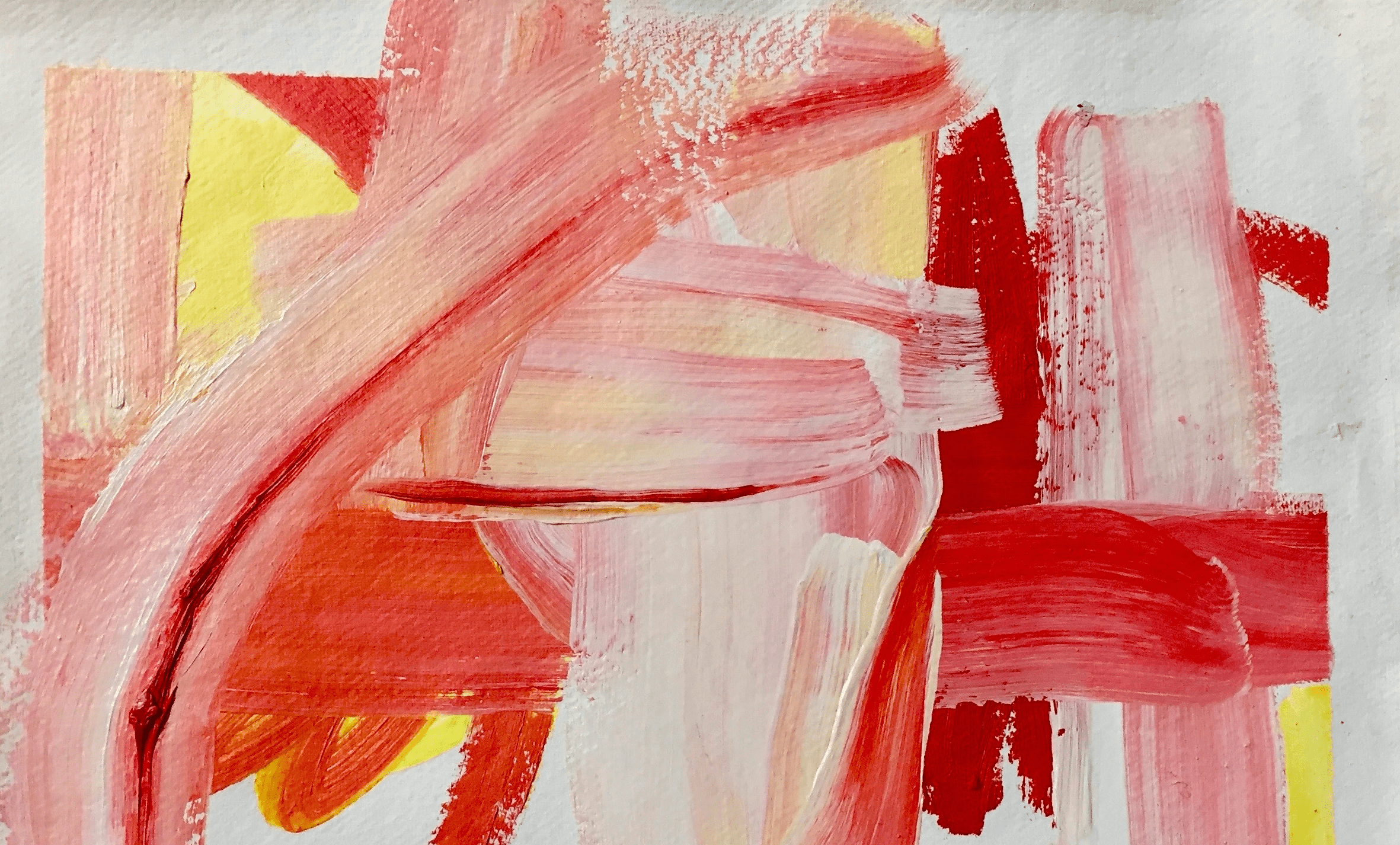

The assertive and confident brushstrokes of London-based artist Kate Dunn swoop and dive and demand the viewer’s attention. Her paintings feel rhythmic both in their state on the canvas and through the traces they leave of the artist herself. The colours clash or find harmony within the drama of the canvas, and the journey of the eye feels lyrical and natural.

Kate studied at Central St Martins before receiving a classical training at the Florence Academy of Art. She then returned to London and further study at City and Guilds. Kate has exhibited in Italy and the UK, including The Contemporary British Painting Prize 2018 and The Great Women Artists x Palazzo Monti Residency. She now teaches at The Art Academy and at City & Guilds of London Art School.

Some of Kate’s more colourful paintings, such as ‘Lady Lazarus’ and ‘Engulfing Every Other Orifice’ (a telling name), are brazen in their occupation of space; their rhythms and energy draw you in and keep you there. The paint seems both contained by the canvas and to jump out of it. I love the way in which Kate plays with the shape of the altar piece. To me, it makes the paintings themselves feel all the more subversive and poignant.

What does the notion of rhythm mean to you and your practice?

The first thing I thought is that the whole of a composition, the whole of a painting, is a rhythm. The way your eye flows, the way you read the gestures of the artist’s hands, the pace of the work; it’s all rhythm. Rhythm is indescribable and can be so many different things, but you know when a painting has it and when it doesn’t. I was thinking about Lee Krasner, the abstract expressionist painter. Mondrian said about her paintings that they had ‘strong inner rhythm’. An inner rhythm for artists like Krasner and Mondrian, because they were so anti-observational or representational art, was something to do with a colour or abstraction reaching a state that takes you out of realism.

In terms of my own work, I think about rhythm visually. I often have big swooping gestures that come into the frame from outside. I think those gestures, quite directly for me, indicate an interruption of a rhythm that’s already present on the canvas, and an awakening for the viewer to remind them that it’s part of something larger.

Do you think the rhythm of the artist and the rhythm of the painting are separate things, or do they interact?

I think every painting, even if it’s abstract, is about the relation between body and material. In that way, the artist is always present, even if they’ve died however many years ago. But some rhythms are visible, and some are more philosophical or psychological and relate to the process of painting and making work. For instance, every mark is a repetition of a mark that you’ve seen, made or learned before. There’s also quite often the habitual methods of making that we get into in the studio; the rhythms of daily life. When I arrive at my studio I’ll make a pot of coffee, I’ll move things around a lot. I’m always moving paintings from one spot to another to get to a state where the room feels like it’s in the right place for me to begin the work I’m about to begin.

How do you know when to stop?

It changes with every piece. Quite often I know when a work is done. I have an idea of what I want it to do, and though it will almost never do that, I’ll stop when it’s doing something either close to what I wanted or something else that intrigues me. Or when it’s doing something that I really dislike and don’t understand. I’ve only been happy with most of my work when it’s in a state between turbulence and serenity. Both have to be present. I think that idea of turbulence relates quite strongly to an idea of rhythm, a frenzied rhythm; I’m thinking of Cy Twombly and those big marks. Sometimes one thinks of rhythm as being something fast, but it can also be something very slow.

How much does your classical training [at the Florence Academy of Art] influence your work now that you’ve moved into abstraction?

I was trained to know how to make paint stop looking like paint and make it look like flesh, cloth, drapery, still life. I went to Florence to learn how to use oil paint. My practice now is still essentially about my relationship with oil paint, so in a way it is a complete continuation, even though I’m not using any kind of realistic language. If you look at the shapes and structures that I use, however, they’re obviously referential of altar pieces and things like that, which was what I was surrounded by in Florence. I’m trying to find a genuine enquiry within abstraction, something that felt foreign not very long ago.

What is it about oil paint that attracts you?

I think it’s the most seductive medium you can use as a painter. It can go from buttery to viscid so quickly. Its figural and bodily without the figure having to be present. I always thought I’d be a figurative painter – and I don’t necessarily think I won’t be – and I think it’s about the relation between material and body. For me, oil paint makes the most sense to use. It’s just the most seductive, the juiciest.

If you went back to drawing, do you think the relationship between you and the canvas would exist in a similar way as with oil paint?

No, because a lot of what I’m questioning is to do with colour, mark and texture, and the emotional states you can get to through that experience. In other mediums I don’t think you have those same conversations – you’d have other conversations. I don’t think I want to return to something completely flat yet. I use a lot of marble dust with oil paint which really thickens it. There’s something about thick paint that excites, seduces, and revolts us all at once and I think that’s a hilarious and really human reaction. One of the paintings in my MA show was really, really thick. Everyone wanted to lick and touch it.

Are the dimensions of a painting important to you?

I think about space more and more as time goes on. I’ve been thinking recently about how to make an active space and how to make painting active within a space. The way we interact with paintings now is so passive because we’ve got such an information overload. Even when we’re in a gallery in front of a painting we like, we get our phone out to take a photo of it and walk away. It makes no sense! So I’m trying to think about how to make the viewer actively engage, though I’m aware that this varies from person to person.

In terms of dimension, I prefer to make works that are the same size as a person or larger. I’m interested in playing with the role reversal of who is in power – I want the viewer to feel like they have to actively choose whether to remove themselves or to engage with a work, as opposed to being able to simply walk past it.

I’ve started playing around with installation more with my paintings. In Brescia in late 2018 I did an exhibition as part of a residency where I hung them with big strips of cloth. One of them was really big, and really quite confrontational. I like the idea of the viewer feeling confronted; that’s important to how I want art to move or engage.

Does the time of year impact you and your work?

Yes, definitely. In winter I find that it’s hard to get to the studio, but when I’m there I’m really productive because I don’t want to leave and I end up staying for ages. You don’t have daylight which can sometimes be annoying, but I’ve started moving out of using natural light so much anyway. The colours that you use are also so reactive to the time of year. Generally, I would say I make happier paintings in the summer probably – whatever that means. But I believe that if you’re feeling a certain way it is going to come out in the work, whether your work is about it or not.

And the time of day?

I find that the seasons affect me much more than time of day. I’d love to get to the studio super early but my journey there takes quite a while, so I never arrive as early as I’d like. The beginning of my day starts slowly, then I get really active, and then I slow down again. But I think it’s more about the state and environment that you’re in than the time of day, to be honest. My studio isn’t in my home, however, so someone with their studio in their house might answer completely differently. Quite often I wake up in the middle of the night and I wish I could work then.

Have you managed to make work during lockdown? How have you found it?

I think we’re in constant cycles of escapism. We work, we bake, we clean, we watch Netflix and then we stop and feel the state of things. When we say we’re ‘doing well’ that is because unless we’re directly affected, coronavirus is still a concept to many of us.

On how this relates to making art during a crisis – it’s been difficult, but not negative. Initially I tried to bring the studio home and make big paintings, which was heavy and also logistically challenging as my home space is so much smaller. Gradually I moved into drawing, rediscovering mediums I hadn’t touched in nine years.

I’ve had moments when making feels completely irrelevant. But then they’ve allowed me to see why making is so essential when it does happen. I miss my studio but I appreciate all this time to think.

Have you been part of any online exhibitions? How has that been?

I was asked to take part in GUTS Gallery’s online exhibition WHEN SH*T HITS THE FAN right at the beginning of lockdown. Ellie (Pennick, Guts founder) caught on pretty quick that this was an opportunity to create a new kind of show. She had this jovial set up on opening night, posting the works with intermittent ‘pick up the press release’ and ‘grab a (lukewarm) beer’. It was fun and it meant ‘showing’ with a bunch of artists that might not have otherwise been together.

Since then, everyone has been making online shows. I have definitely got to the point where I miss the material.

Kate’s work is currently on show as part of A Dream is Not a Dream, an online exhibition organised by Purslane with proceeds going to the Stephen Lawrence Charitable Trust.

You can see more of Kate’s work on her website: www.katedunnstudio.com

Image credits (from top):

1. Kate Dunn, Melba [detail], oil paint on paper, 2019

2. Kate Dunn, Englufing Every Other Orifice, oil paint, acrylic paint and marble dust on panel, 2019

3. Kate Dunn, Barbie’s Maesta, oil paint and acrylic paint on panel, 2019

4. Kate Dunn, Lady Lazurus, oil on panel, 2020

5. Kate Dunn, Slap Me Silly and Call Me Sally, mixed media, 2018

6. Kate Dunn, You Could Have Easily Had Me, oil paint and acrylic paint on panel, 2019

7. Kate Dunn, With Curious Eyes and Sick Surmise, oil paint, acrylic paint and marble dust on panel, 2019

8. Kate Dunn, Pinch, oil paint on panel, 2019

9. Kate Dunn, Tabby Wants A Tickle, oil and acrylic on panel, 2019

10. Kate Dunn, Sticky Fingers, oil paint on paper, 2020

11. Kate Dunn, Melba, oil paint on paper, 2019

This is part of RHYTHM, a section of The Learned Pig devoted to exploring rhythm as individual and collective, as poetic and biological, and the ways that rhythm dictates life. RHYTHM is conceived and edited by Rachel Goldblatt.