New York-based artist Patrick Jacobs unfolds a carefully crafted stage that invite us to seek wonderment in both natural and unnatural landscapes that might easily be overlooked. Painstakingly constructed models display different species of fungi or weeds in the foreground. Each leaf and blade of grass is shaped to situate a humble scene. Jacobs imbues them with this sensitivity through the dioramas placement within the walls, the specific optical lenses used to view the secret stages, and the lighting that illuminates the three-dimensional like paintings.

Natural history dioramas originated out of the late 1800s and their influence can be seen in the use of virtual reality (VR) technology today. What is missing out of VR is the hand and the impact of performance to direct the gaze. The physical stage entices our phenomenological sensibility. Jacobs incorporates this idea into his work, not simply in terms of the drama of their presentation, but also through physical performances and staged scenarios. Some of these include Sleeping Magician, a work staged with a magician sleeping in a cot on a platform in a gallery space along with his accoutrements used for magic tricks. Or Cancelled Show / Celebrity Appearance where Jacobs created a performance with celebrity lookalikes along with their escorts, limousine driver, and paparazzi during a gallery opening.

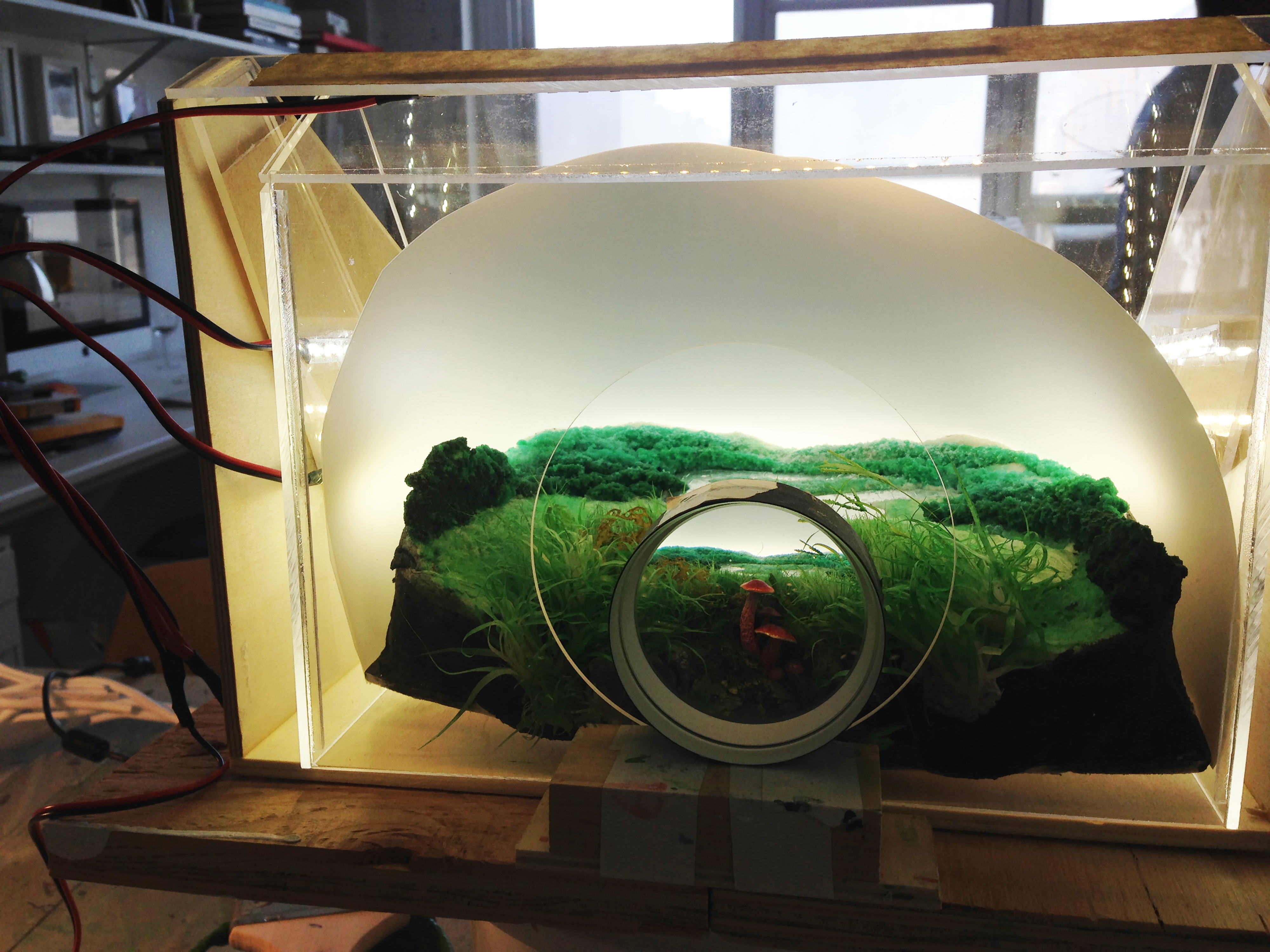

I met up with Patrick at his Brooklyn studio to have coffee together and for him to give me a tour. When I entered his studio, it felt as if I was entering “backstage”. Everything that would normally be hidden away behind walls in a gallery or museum space unravels to backbone diorama structures, cut outs of tiny leaves, strands of LED lights laying around, mud mounds, and little tweezers ready for use.

Jacobs explains to me how the idea and interaction of performance provides variations on aspirational themes and transcendence throughout his work.

You often use BK7 optical lenses, also known as borosilicate-crown glass. This type of glass has an index of refraction similar to water. When people look through the concave glass to view your landscapes, everything appears much smaller than it is. By refining the image presented to the viewer, the lenses also allow for another alternate reality to come alive that is magnified and brought to our awareness. How did you begin using this specific type of lens in your work?

I found this method of working by chance. While in graduate school, I wanted to build a very large fiberglass sculpture for a show at a student art gallery. To get a sense of the scale of the object in the space, I made a small architectural model of the gallery and placed a miniature version of the artwork in it. But, what I wanted to achieve with that model was to be transported into it. I took a small concave lens that I happened to have in my studio from a local science surplus store, cut a hole in the wall of the model, and peered into it.

The result was a kind of vivid, tactile reality, a space that you could not touch directly but you could both perceive in your mind and feel in your brain. I shifted to building the scenes as I looked through the lens, so that the construction, lens and image were intrinsically bound. It wouldn’t work to make a landscape and then seek out a piece of glass to define it. In a sense, the work arises through the medium of the lens.

The strength of the lens bears a direct relationship to the size and scale of the scene, as well as the amount of detail required. A negative focal length makes the objects appear smaller the further away from the lens they are placed. If it is too weak, the result is little better than looking through a flat pane of glass. If too strong, the eye no longer perceives three-dimensional space clearly – it becomes, to use your comparison, watery. So, there is a fine balance between the illusion of distance and perception of three-dimensional space.

Where does your interest in performance, or the documentation of performance in your work originate?

Performance gave me the chance to create an action or situation in which the banal is elevated in some cases to the supernatural. The events were staged in different ways, sometimes using props or performers and documented using different media. Sometimes the photograph or video was meant to be the work and other times it was the event itself.

I noticed on your book shelf the museum monograph of Bruce Conner, It’s All True. I had an opportunity to see the exhibition at SFMOMA this past year, and I am curious if his work influences your ideas of performance in any way?

Conner’s work is extraordinarily diverse. I’ve always found his ability to use a new form or material no matter how seemingly contradictory in the pursuit of an idea very inspirational. In my own work, it’s been helpful for me to see performance in terms of kinetic sculpture or three-dimensional photography in motion or film and video as painting. Conner’s work is an affirmation of how we can (and should) think free of boundaries.

What are you currently working on?

I’m working on a series of sculptures of mud, sticks and stones called “Les Fleurs du Mal” after Charles Baudelaire’s eponymous volume of poetry. They suggest crude plant, animal or human forms. I’ve started casting them in bronze to retain a dark, heavy, and primal quality. Well, I’m very excited to see where they end up.

The pest control resource manual Ortho Home Gardener’s Problem Solver influences the scenes that you choose for the viewer to investigate. You have a garden next to your studio, – what do you use it for? And do you consider weeds, fungi, and insects to be pests in the first place?

I have a small rooftop garden off my studio, which includes some native plants, flowers and weeds. Occasionally, I’ll find mice and snails burrowing or munching leaves. I’ll divert or trap and carry them away to the park. I like to attract bees and butterflies, in terms of insects, but I do draw a line with aphids, which can decimate an entire garden. In that case, organic pest control is a last resort.

I’ve always found weeds (outcasts from the ideal landscape) and fungi (hybrids of animal and plant, sometimes poisonous or hallucinogenic) particularly curious; they constitute a kind of menagerie of anti-heroes, simultaneously cryptic and exuberant, fragile and obstinate, indolent and aspirational.

Patrick Jacobs is represented by Pierogi Gallery, New York. For more information on Patrick Jacobs, please visit his website: www.patrickjacobs.info