On my way back from the gallery I took a train and experienced the usual flicker of annoyance when the conductor began speaking to us as if we were in a plane. He gave the estimated arrival time, pointed us to the safety notices, alerted us to any suspicious looking bags. It was the usual bullshit. There was nothing very risky in travelling home from London to Brighton. Except, except…

Except this: for some poor soul just outside our terminus, 22 April 2014 was a fatal day. The conductor came back on the intercom and informed us of a person “under a train”. We were stopped at a nowhere station. He warned of open-ended delays. He suggested we might best get home by taxi. He gave us a code with which we could claim refunds. As more and more passengers bailed in search of a mini-cab, there was a sense that we remainders were keeping the faith. But for what?

It was fortunate I had plenty to occupy me. Earlier that afternoon I visited a show at England & Co in Fitzrovia. Rising star of hazardous sculpture, Ben Woodeson, was showing his work alongside that of his late and larger-than-life grandfather Jack Bilbo. So I had to ask myself: what would Woodeson have made of this trip? And what would Bilbo, a deportee from Nazi Germany, have made of the chaotic lateness of British trains?

What would Bilbo, a deportee from Nazi Germany, have made of the chaotic lateness of British trains?

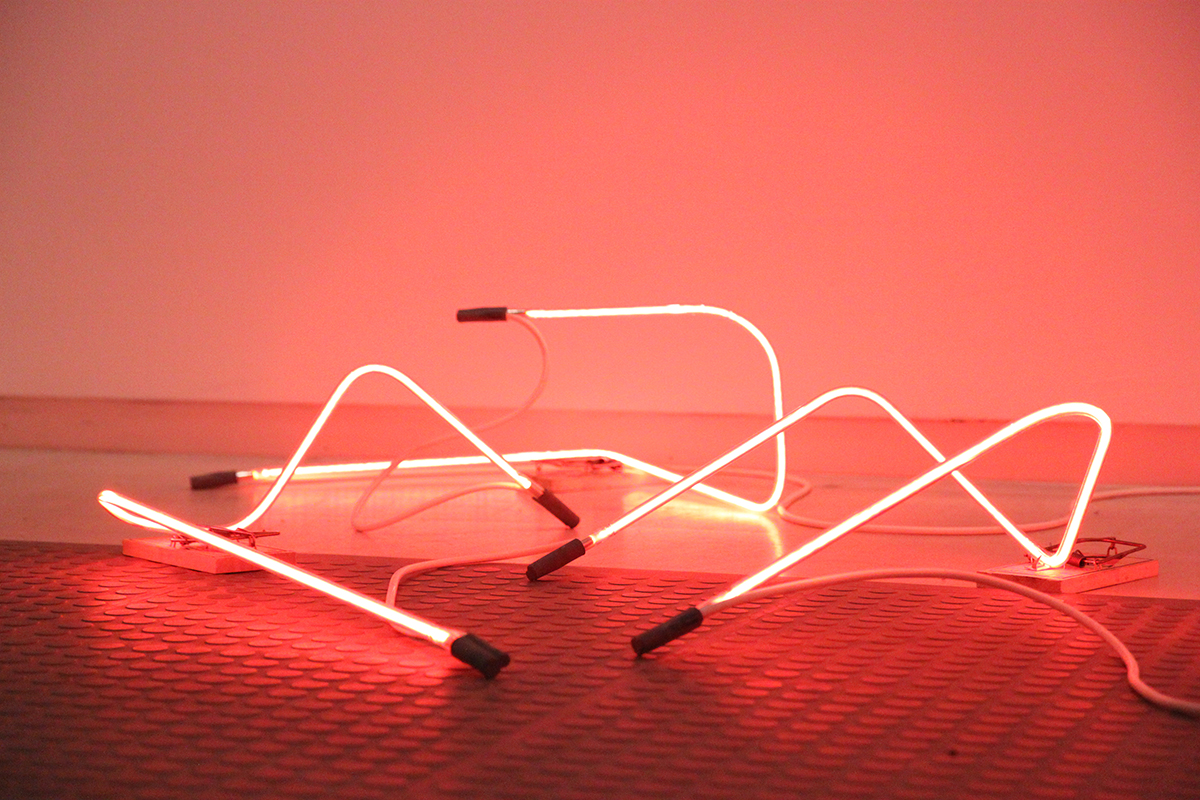

Thanks to Woodeson’s sculpture, perhaps I was already feeling fragile. Fresh in my mind was a warm and inviting nest of neon bars, each one wired to a rat trap; a toxic looking entanglement of a bright-coloured clothes horse and a knot of ventilation tubes; and a tornado of black cable which looked like it could choke a person. I tried to take heart from the black and blue ink drawings by the older relative. They were fearless, direct, and perhaps two-fisted pieces of work. He has his own visual language, with overwrought lines, dark shading and a contrasting fetish for delicate eyelashes. Text finds its way into these claustrophobic doodles. He makes the case against the state, against the military-industrial complex, against the bourgeoisie. It rather seems he might have understood the delays to my journey all too well.

Later that week, I speak to Woodeson on the phone. “I have a personal aversion to barriers,” he tells me. But he’s speaking about galleries not stations. To date, none of his work has called for a barrier. But we are soon talking about his 2010 Spinning Cobblestone, a pendulous eight kilo weight that could kill an onlooker. He tells me: “I’m not a psychopath”. He mentions security guards rather than guard rails. And he also says: “That work would need to be seriously controlled if it would be seen”.

Woodeson tells me that in civilian life, he is quite risk averse. But I’m interested to hear that he cycles in London and how a few years ago, a near fatal collision with a car took him out of commission for five months. “I went face-first through the side window . . . and, so, collarbone in operation, and cut open neck. Quite traumatic.” And had he been a moment earlier, he would have gone under the car, and good night.

But Woodeson’s work has got no safer, whether balancing sheets of glass, rotating blades at speed, or using a drill bit to whip cables along the floor. “When I start to get a sense of adrenalin or a sense of almost unease, that’s when I start to think I’m getting somewhere,” he says. And now that he’s found a niche –physical danger in art – “There’s more works than I could ever possibly manage to make”.

The artist speaks of his vocation as the one occupation which has never made him bored. “There is this constant challenge and enquiry,” says Woodeson: “your relationship with your materials and space and physics and gravity and friction. That deepens”. If there is aggression in the work, most of us can relate to that. “I make work rather than going out and kicking someone in the balls.”

And while I don’t exactly kick my interviewee in the balls, I do throw him an unfair curveball in a question about today’s nanny state versus the Nazism that his grandfather endured. Woodeson gamely mulls it over, before saying that we’re lucky to live in a democracy of sorts. “On the one hand the nanny state is an irritation,” he begins, then quickly points out that the revelations about the NSA are part of the same picture: “part of keeping society in fear, because then we’re easier to control”.

This being peacetime, we are back in Brighton. All remaining passengers disembark with a mixture of relief and righteousness.

My train journey takes 90 minutes longer than usual. Between updates about the progress of engineers, I read the slim catalogue, and wonder at Bilbo’s life story. And to think where he struck up a friendship with Kurt Schwitters: an internment camp on the Isle of Man. But this being peacetime, we are back in Brighton. All remaining passengers disembark with a mixture of relief and righteousness.

The conductor is on the platform and I witness a fellow commuter pump his hand in gratitude. His frequent announcements and updates were, after all, a comfort rather than a trial. Someone else has died here and today it was none of us. It seems, in a blur of station lights and bustle, that this public ambassador for the indefensible has been our salvation, of sorts, of sorts. And I think once more of Woodeson, revealing danger rather than creating it.

Twelve-Fisted Boxing Caterpillar is at England & Co, until 3rd May 2014.

Postscript: through better luck than judgement, the individual who went under a train in Brighton on the date given actually survived.