When I first walked in, I didn’t get it. The walls of the first gallery are covered in neon orange paper. Obviously this was done for effect, but what effect, other than mild visionary discomfort, I could not think. And there was a man in a chair. Not a real man in a chair (although there was one of those too), but a stuffed, headless, model of a man, in a chair. This felt significant, but I wasn’t sure why.

I only realised the parallel between this stuffed and headless model and the real man, sitting in the chair, once I had wandered the full five rooms that Joëlle Tuerlinckx’s exhibition takes up here at the Arnolfini. This seems to be the point of the show: it is not about the individual pieces per se, as much as their cumulative effect. My sense of confusion only began to subside once I reached the third room, but it wasn’t until the fifth and final – also the smallest and the simplest – that the eureka moment came. This shift of perspective inspired a re-visiting and re-experiencing of all the preceding rooms, accordingly. But let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Suffice to say that to enjoy this exhibition you have to stick with it.

Joëlle Tuerlinckx’s WOR(L)D(K) IN PROGRESS? is not just an exhibition; it is an installation of work that engages the audience as participant in a performance of shifting scale and perspective. The wor(l)d(k) emerges, as the carefully formed title suggests, in relation. There is no simple mirror of work being held up to the world here. No easy split between world, word or work. Each is infused with, or splintered up in, the other. The effect of this splintering of mirrored fragments is, unsurprisingly, profoundly disorienting. This is the real gift of Joëlle Tuerlinckx’s exhibition.

From my initial scouring of the first (orange) room, I manage to glean that there is some sort of play on perspective going on: oversized printed pages relating to geometrical measurements, rulers of various sizes stuck to the wall, a giant black Polaroid, a ladder to nowhere. This theme continues on the second floor, which, if anything confuses me still further. The message here seems to be even more oblique. The space is very bare and airy. A seemingly random thread hangs from the ceiling: it makes me wonder whether the windows (or world beyondthe window) are in some way included in the work ‘on display’. There’s a pointbeing made about countries, and their various relations to each other, in the photographs of world leaders – but I didn’t really understand it. The third, and very busy, room is where the penny drops: the arrangement of space is political.

The floor in the third space is filled with objects;

it’s a gallery equivalent to a child’s playroom.

The floor in the third space is filled with objects. In a gallery equivalent to a child’s playroom, each object invites a different perspective or way of engaging with space. This invokes a contrapuntal drive to throw yourself into this space with relative abandon, to play and explore what’s on offer, and to hold your body back from doing just this, in the fear, common to most gallery experiences, that bodily engagement with this work might break, tarnish or in some way devalue the art’, such is the reverence for the gallery temple. This is all part of the reflective experience encouraged by this work: how are you inhabiting this space? Why are you inhabiting it in this way? Inhabiting is therefore exposed as a form of sense-making; a bodily formation of thought. Only once we feel happy about how and why things fit together can we abandon ourselves to or embrace the spatial politic.

In this third room there is another ladder, echoing the position of the ladder in the (orange) room below. This time the ladder leans against a billboard poster of a lady with her legs akimbo. This image has been so magnified that you can see the pixels within the pixels. Approaching this image, to examine the pixels more closely, immediately feels taboo. There is a shadow cast by the ladder. This feels important. The ghosts of these objects are the other occupants of this space. A ghosting that suggests the internalised perceptions of the work that continues in our heads, legs, hands and feet. We internalise these spatial politics: the organisation of space and perspective determined by the arrangement of these objects casts an internal shadow.

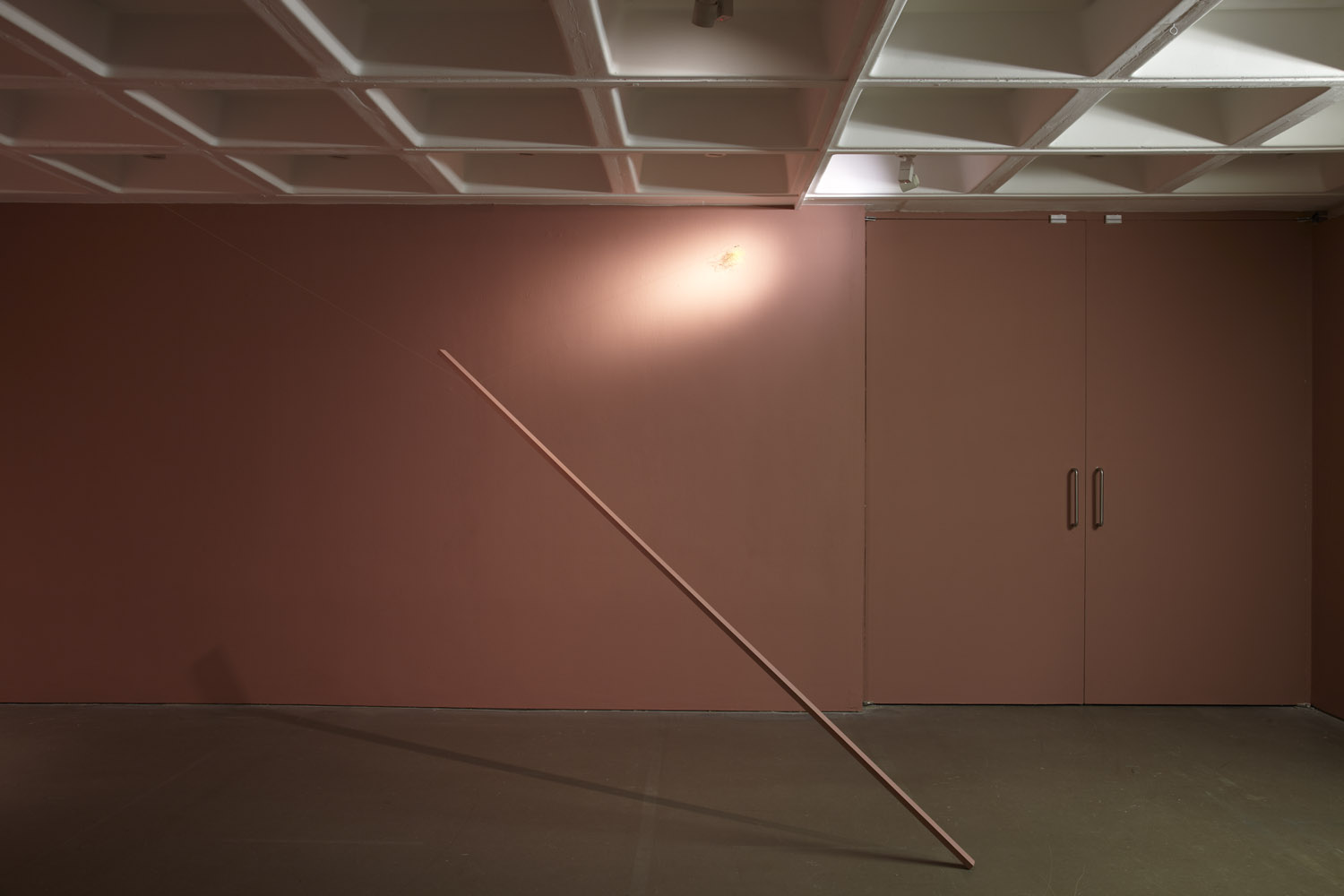

There is another space leading off this main room, in which a long stake leans on a diagonal, held up by wire. You can walk around this stake, and as you do so, its shadow passes over you. You see other people doing the same, and you see how their body is cut by the sharp line of the stake; how its shadow ripples in response to the particularity of their form. The set-up is simpler; the message is clearer.

This progressive simplification of form and function is exemplified by the final space in this show: a small room, on the top floor, entirely covered in neon yellow paper. But this time the neon yellow side of the paper is facing outwards, towards the wall. The pages are loosely enough arranged for us to see the reflection of the neon yellow on the painted white brickwork beneath. This time, we are inside the neon yellow box. The parallel between this and the neon orange paper of the first room becomes clear. To begin with we were inside a room, but on the outside of the exhibition’s modus operandi, looking in, trying to penetrate the meaning of this neon orange box. Now, in the final space, having inhabited the various organisations of objects and assimilated their respective arrangements of space, we have been assimilated into and are now part of the neon box of the exhibition. Just like the invigilator and his uncanny counterpart, in the first orange room, we are now part of the exhibition and the exhibition is part of us. Inhabiting space requires sense-making; having made sense of this space with our bodies and our minds we will now take this sense (and therefore the exhibition) with us, as mobile exhibits.

The exhibition redeems the audience member from

the passive role of ‘viewer’, propelling us into an active

understanding of our role in this performance.

This is the type of work that elicits a continued questioning beyond the gallery space: how are we being formed by the arrangement of the streets, buildings, places of work and home that extend beyond this exhibition space? What spatial politics have we already internalised and in what ways are we complicit in those that stretch far beyond us? How, in re-organising our habitual occupation of space, can we too become agents of political change?

Joëlle Tuerlinckx’ WOR(L)D(K) IN PROGRESS? redeems the audience member from the passive role of ‘viewer’, propelling us into an active understanding of our role in this performance and our potential to resist or redefine this performance according to our use, or re-use and occupation of space. To echo the epic and formative words of Luce Irigiray’s early feminism, it is in resisting and reforming the ‘normal’ organisation of space that we’re able to frustrate the theoretical machinery of how and why we are formed and informed. This exhibition realises this link between physical and mental (re)organisation: each is splintered up in each, there is no simple mirroring.

Joëlle Tuerlinckx – WOR(L)D(K) IN PROGRESS? is at Arnolfini until 16th March 2014.

All images: Joëlle Tuerlinckx, WOR(L)D(K) IN PROGRESS?, Arnolfini, installation view, 2013. Photos Stuart Whipps