Human Marks in the Ice

Ships fighting against a freezing sea. Masts and ropes caked in ice. Crews of men hauling sledges over crumpled and broken landscapes. These are the mental images conjured when many think of the Arctic and the history of its exploration by Europeans, Russians and Americans. However, this is not the only human history of the Arctic – a polar region slippery to define but broadly consisting of the Arctic Ocean and parts of Alaska, Canada, Finland, Greenland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden. Indigenous communities – the Inuit, Eskimo, Sami, Nenets and many others – have a long history of living in and around the Arctic, using its bounty to sustain themselves and drawing their culture and folklore from its landscape and seasonal rhythms. Elsewhere, in the present day, the idea of the Arctic has also become more multifaceted. Although exploration to find trade routes and resources is still important, ideas formed around borders, civil infrastructure, scientific research and biome conservation, among other concerns, now shape our imagination of the Arctic.

Crucially, both the distant past and the contemporary world as sketched out above are connected by the history of exploration. The work of explorers – not to mention the traders, hunters and trappers who, historically, followed them – is a bridge between these two eras. The major period of exploration by Europeans, Russians and Americans, stretching from the fifteenth century to the early twentieth century, had a huge impact on indigenous societies across the Arctic. The arrival of Western explorers broadened the horizons of these cultures, but also introduced new tools, mechanisms of economic exchange and diseases – factors that would reshape populations and create conflict between communities for generations to come. These dynamics have reshaped the Arctic world of the indigenous peoples as we see it today.

Moreover, the territories explored and endeavours undertaken by explorers have had a lasting impact on our contemporary understanding of, not just the Arctic, but the world around it. The border claims of modern nations are underpinned by the maps, lost ships, cairns and claims of Victorian explorers; strands of scientific analysis, including those relating to climate change, have been opened up and evidenced by the findings of historic expeditions; and Arctic wildlife still bears the scars of those who made the most of adventurers’ finds.

In the contemporary era, the basic motivation of European and American explorers – the pursuit of resources and trade routes in order to gain financial and political advantage – is fundamentally unchanged. However, the search has shifted from a hunt for gold to a race for ‘black gold’ (oil). The Arctic continues to be reconfigured by this desire for wealth, which is also, simultaneously, inspiring creativity, cultural growth and even the development of spiritual attachments to the land, as it has done for thousands of years.

Blank Spaces?

Today, inhabitants of much of the world still think of the Arctic as a blank space – an unspoilt, unpeopled space of spectacular ice formations and dramatic seascapes. This is far from the reality of the modern Arctic, which is peopled, holds many unique cultures and is also a site of intense political and commercial interest for the wider world. Moreover, the Arctic has long been this way. During the time of the Roman Empire the silk roads, which acted as trade routes connecting the Far East with the Mediterranean, carried amber and furs from the Arctic across the world. The high north was already part, albeit on the extreme borders, of a continent-spanning trade network.

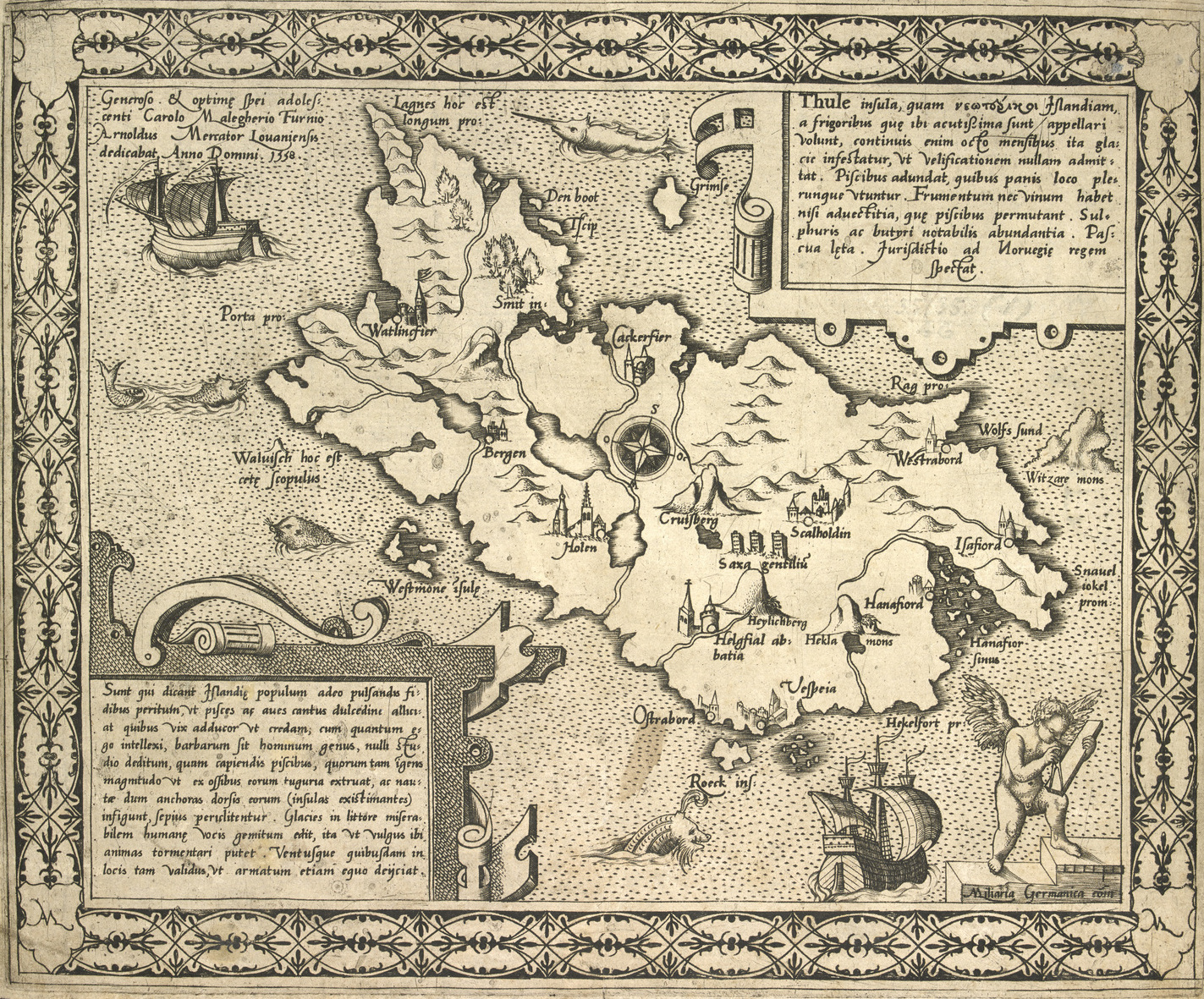

In the fifteenth century, the exploration of the Americas by Christopher Columbus changed the operation of the world’s trade networks; northern European countries, afraid of being sidelined and perhaps even threatened by the increasingly affluent Spain and Portugal, looked north for solutions. Looking to gain a trade advantage, not to mention precious resources and other trade opportunities, England and other northern European countries started to look for Arctic trade routes, and the search for the Northwest Passage began. The Northwest Passage was a sea route over the landmass of North America that, it was hoped, would be simple, ice-free and shorter than the Atlantic routes currently monopolised by the Spanish and the Portuguese. Others looked to a Northeast Passage – running via seas over the Eurasian landmass, or via the North Pole – but all of those searching for these routes hoped to find the same thing: an advantage over their competitors.

Explorers including Martin Frobisher, William Barents and James Cook began to journey north in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and come into increasing contact with the indigenous communities of the Arctic. This was the beginning of an intensification of the wider world’s interest in the Arctic, an interest that would change the north and how it was viewed by people to the south.

Populated Places with Rich Cultures

Across the Arctic there live indigenous peoples with rich, distinct and historically deep-rooted cultures,who have lived there since long before Europeans took an interest in the north. Their cultures and traditions have been handed down over hundreds of years through oral testimony and material culture, an example of such a culture being the Inuit carvings now so popular with art collectors all over the world. Inuit print culture is also extremely popular today, having seen explosive growth as an art industry in the twentieth century. Before this, Europeans had attempted to record Inuit culture in forms they regarded as more tangible, such as the printed word and artistic illustration, and some of these objects still survive today.

Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait (Greenland Legends, 4 vols., 1859–63,) is one such object, compiled and edited by Hinrich Johannes Rink, a Danish geologist, scholar and administrator, working in Greenland in the mid-nineteenth century. The book’s focus is on Inuit history, culture and tradition and the four volumes tell various stories through text, in Kalaallisut (Western Greenlandic) and Danish, and prints, by Aron Kangek, a young hunter who went on to become an important oral historian for the region. The scale of the work and the variety of its content display the richness of Greenland’s Inuit culture, as well as the depth of its historical memory.

Of particular note are the accounts of Inuit interaction with the Norse settlement that existed in Greenland between the tenth and fifteenth centuries. Originally founded under the leadership of Erik the Red, this settlement existed alongside Inuit communities before eventually disappearing, possibly due to climatic change that caused crops to fail and the landscape to become inhospitable to settlement. Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait recounts stories of, at different times, both cooperation and conflict with this settlement. Such cultural artefacts and histories are not unique to the Inuit of Greenland, nor to the Inuit as a whole. The culture of pan-Arctic indigenous peoples is repeatedly shown to be diverse and robust, not to mention constantly marked by the encroachment of European peoples. Indeed some peoples, such as the Sami, have had an impact in the opposite direction.

Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait highlights the fact that the Arctic explored by Europeans from the fifteenth century onwards was far from an empty land. Rather, it housed rich and diverse cultures that had seen Europeans come – and go – before.

A Feel for the Landscape

Finding one’s way in a landscape is fundamental to survival and cultural development for peoples all over the globe In the Arctic, where changes in weather are not only dangerous but can alter the features of the land, being able to navigate is particularly important. Indigenous Arctic cultures have used various navigational methods – in particular, reading the clues and marks left by weather, which provide points of orientation – but maps are still an important part of their wayfinding methodology.

Indigenous mapping of the Arctic has taken a variety of forms, including spoken description and ephemeral maps carved in ice and with stones – both practices that are important to indigenous cultures across North America. Within this tradition, the process of mapmaking is more important than the map object: it is a way of communicating knowledge, forming bonds between people and reaffirming the human relationship with land and sea.

Maps have also been carved in wood, as evidenced by surviving nineteenth-century maps of parts of the East Greenland coast. These maps are designed to be rotated and felt by hand, each notch and curve represents not only a ‘bird’s eye view’ of the coast, but also gives a sense of it in three dimensions. While a European tradition of mapping would recognise the function of these objects, the way in which they are used underlines a fundamental difference between the two cultures in terms of relationships to land and sea. For Europeans, the map is more than just an object of practical use: it represents a form of domination and control. The ability to see the land in its entirety, from the perspective of a god, allows the viewer to lay claim to it, as we will see later in the propensity of European explorers to leave their names, and the names of their sponsors, strewn across the landscapes they mapped.

By way of contrast, Inuit maps are designed to be held in the hand and felt, and represent a more tactile relationship with the landscape, one in which humans and their bodies are in contact and collaboration with the land. These maps, facsimiles of which are held at the Scott Polar Research Institute, Cambridge, were carved by Kunit fra Umivik and collected by the Danish explorer Gustav Holm in the 1880s. As well as illustrating an important Inuit practice, they also evidence the dynamics of exchange that began to seep into Inuit relations with Europeans once explorers, traders and scientists started to work in the north.

These Inuit maps are slightly abstracted to the eye (although no less authoritative) and do not offer the sense of visual control experienced when looking at European maps. Thus, they illustrate these two cultures’ different perspectives in relation to the Arctic land: that of Europeans, which seeks to define, claim and dominate; and that of the Inuit, which seeks to relate, use and thrive.

This is an edited extract from Lines in the Ice: Exploring the Roof of the World, by Philip Hatfield, British Library, £25

Image credits (from top):

1. Bradford’s photograph of the crew of the Panther with the spoils of a bear hunt, 1785

2. Illustration from Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait [Greenland Legends] (1859 and 1860 volumes)

3. Illustration from Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait [Greenland Legends] (1859 and 1860 volumes)

4. A map of the Island of Thule, by Arnold Mercator, 1558.

5. Ammassalik map carved by Kunit fra Umivik. Greenland National Museum and Archive

![Lines in the Ice - Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait [Greenland Legends] (1859 and 1860 volumes).](https://thelearnedpig.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/01-D40110-30-HR.jpg)

![Lines in the Ice - Kalâdlit Okalluktualliait [Greenland Legends] (1859 and 1860 volumes).](https://thelearnedpig.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/D40110-32_edit.jpg)