In 1958, the great Austrian artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser published the Mould Manifesto against Rationalism in Architecture. In it he declared, with characteristic chutzpah, that:

“Only the engineers and scientists who are capable of living in mould and producing mould creatively will be the masters of tomorrow.”

As far as we’re aware, few have taken up this provocatively prescient call to arms, until now. Kathryn Fleming is one of a number of artists and designers beginning to explore the possibilities of mould. Riffing on the notion that our moods are strongly influenced by the bacteria in our guts, Fleming posits Gut Reactor: three species of “Fungus Domesticus” which produce airborne spores to stabilise our emotional states.

Gut Reactor is just one of a number of works by Fleming that look to combine speculative design with the more playful elements of synthetic biology in order to explore our understanding of the natural world. Fleming’s work – which includes an orchid influenced by female human hormones, several designs for new wild animals, and a reworking of London Zoo into Regent’s Park of Evolutionary Development – is both a comment on existing relationships between the human and the non-human and a prompt for how they could potentially be rethought in the future.

We first came across Fleming’s work via the Next Brave New World exhibition at arebyte gallery in east London and subsequently caught up with her to find out more.

The Learned Pig: You describe yourself as “a multidisciplinary designer” but you seem to work a lot with science, especially biology. What can the creative disciplines such as art and design contribute to science (and our thinking around science) that perhaps scientists cannot?

Kathryn Fleming: I believe that the sciences and the arts were never meant to become as divided or separated as they have become. While modern sciences strive for ‘objectivity’ through the rigorous use of the scientific method, paradoxes consistently arise in both science and mathematics that disprove and contradict each another. Whereas scientists often seek to arrive at a single ‘truth’, the inherent subjectivity of art seeks to address truth as a more relative understanding. The necessity of storytelling and narrative within the arts and humanities also allows for a level of inherent complexity which activates our human capacity to possess negative capability – described by John Keats as “when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason”. Instead of seeking one correct answer, artists and those within the humanities must often imagine a range of possible answers. There are now fields within science and mathematics that also reinforce this type of speculative thinking – such as quantum mechanics and information theory – but we still see a divide between the two disciplines.

The Design Interactions programme at the Royal College of Art, which I just graduated from, is definitely seeking to create a new type of ‘Third Culture’. Students in this programme have hugely variable backgrounds spanning anthropology to computer engineering and include fine artists as well as product designers. Headed by Anthony Dunne, the programme emerged from an older department called CRD (Computer Related Design) that was an offshoot of the Design Products Department. With a continued emphasis on research into the potential use of emerging technologies, combined with students from multiple disciplines and backgrounds, the work and the thinking that goes on within Design Interactions is inherently trans-disciplinary. When asked what we are studying, many of the students genuinely don’t know how to define it, precisely because the work we do doesn’t follow traditional boundaries.

The Design Interactions programme at the Royal College of Art, which I just graduated from, is definitely seeking to create a new type of ‘Third Culture’. Students in this programme have hugely variable backgrounds spanning anthropology to computer engineering and include fine artists as well as product designers. Headed by Anthony Dunne, the programme emerged from an older department called CRD (Computer Related Design) that was an offshoot of the Design Products Department. With a continued emphasis on research into the potential use of emerging technologies, combined with students from multiple disciplines and backgrounds, the work and the thinking that goes on within Design Interactions is inherently trans-disciplinary. When asked what we are studying, many of the students genuinely don’t know how to define it, precisely because the work we do doesn’t follow traditional boundaries.

Like Anthony Dunne’s approach, Victoria Vesna, Chair of UCLA’s department of Media Arts also sees the merit of merging the arts and the sciences. In an essay she wrote entitled Towards a Third Culture or Working in Between, she proposes that:

“Artists using technology are uniquely positioned in the middle of the scientific and literary/philosophical communities, and we are allowed ‘poetic license’, which gives us the freedom to reinforce the delicate bridge and indeed contribute to the creation of a new mutant third culture.”

My interest has less to do with improving communications between human disciplines, and more with helping to bridge the disconnect between humans and other species.

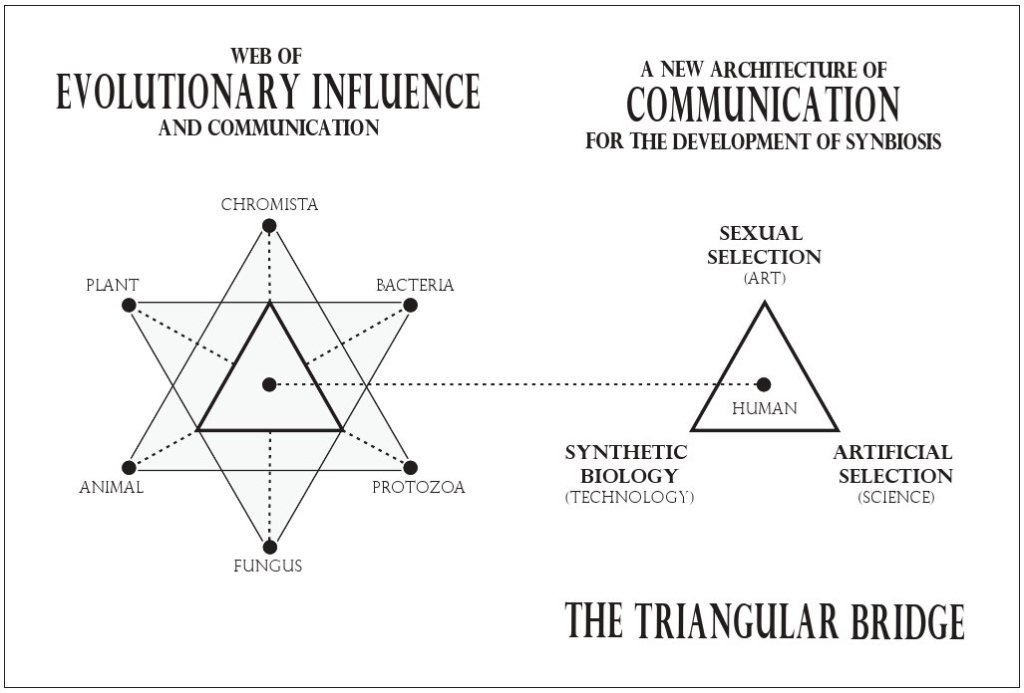

I was personally inspired by her idea of creating a ‘triangular bridge’ to both stabilise and unite the sciences and humanities through artistic use of technology. My specific interest has less to do with improving communications between human disciplines, however, and more to do with helping to bridge the disconnect between humans and other species. If we see genes as a basic unit of biological information, then perhaps genes developed and evolved through sexual selection, artificial selection and synthetic biology could be the artistic, scientific and technological tools humans can use to engineer communication with other species and develop new symbiotic /cooperative relationships. [See diagram below]

TLP: How have human relationships with animals changed over time (for better or for worse) and how do you envisage these relationships developing in the future?

KF: My perspective on human-animal co-evolution definitely sits more firmly in the optimistic portion of possible futures. This is a very intentional choice. While cautionary tales about what could go terribly wrong in this regard have prompted people to consider the topic of genetic engineering more critically, I think this approach overlooks the most compelling aspect of our relationship with animals. The thing I have found while working in the field of human-animal interaction is that it is an almost universal phenomenon that humans are naturally and instinctively attracted to animals. At a very deep level, animals make us human; they are the ultimate ‘other’ through which we create a basic dialectic to place ourselves within a larger context biologically and culturally. We are not and cannot be separate from them.

At a very deep level, animals make us human; they are the ultimate ‘other’ through which we create a basic dialectic to place ourselves within.

My hope is that using emerging technology, including synthetic biology, we can also try to design more co-operative relationships back into our interactions with animals. Not only do I think that increased contact with animals is good for people, but like technology has given us new capabilities, animals also offer capacities far beyond our own. Living in today’s Information Age means that communication is not only easier; it’s paramount. If we view genes as the most fundamental of all information, then being able to share and exchange genetic information between life forms is the ultimate form of communication. Biological technology then offers humans the potential ability to be connected and communicate with animals in new ways. This is VERY exciting!

TLP: There is a strong correlation that connects all artists/authors/creators with an idea of god. Is there a worry that with “biological design” there is a tendency for the designer to see themselves “in god’s image” in a way that perpetuates humanity’s perceived superiority over nature?

KF: Ideology is much like biology in that it is subject to change over time. The largest changes in human evolution and ideology seem to have been guided by the development of technologies that help humans to exert influence on other forms of life and their environment. However, I don’t think we often consider the ways in which those forms of life have also developed techniques and adaptations that have altered and influenced us. It is a two way street. Michael Pollan’s book, The Botany of Desire, looks historically at plant cultivation and takes the view that plants have exploited us just as we have exploited them. Although we like to see ourselves as existing outside of nature with the ability to dominate it, this outlook entirely overlooks our innate dependence on it. Not only are we dependent on nature for basic biological survival, but also for much of our experience of pleasure. This is why I think that when considering biological design it is critical not simply to consider the results as useful products, but to view them as independent life forms that we want to have cooperative and fulfilling relationships with.

TLP: You describe your work as designing “visions”. To what extent are they visions that you would actually like to see realised? How ironic or ambivalent is your stance in relation to your own designs?

KF: I definitely did not create this project with the intent that these creatures would actually be seen as sincere design proposals. Instead they are meant to encourage viewers to think about the impact that wildlife has on the human imagination. Up until now synthetic biology has focused on creating functional and purposeful things. The idea behind golden rice (rice that is engineered to synthesise beta carotene) is an excellent example of a product of this type of outlook. If we are meant to have solely quantifiable and monetary benefits from the products of genetic engineering, then it would seem that wildlife would be the last thing we would attempt to design. For most intents and purposes, wildlife is useless in that way. However I think that having an overly functional perspective on biological design overlooks the beauty and delight that exist when encountering other living things. This aspect of biology should not be underestimated because it has a massive effect on the way in which we perceive and experience the world and on our emotional connections to other forms of life.

While we selectively breed our domestic animals for particular traits, we literally do the opposite with captive wild animals.

Aside from the animals themselves, I also focused on redesigning the institution of the zoological garden and the larger institution of captivity itself. I find zoos depressing places. Yes, it can be thrilling to encounter so many living species, but because these animals evolved to survive in the wild, their lives in zoos are completely artificial. We are influencing the evolution of zoo animals through captivity itself as well through highly designed breeding programmes. While we selectively breed our domestic animals for particular traits, we literally do the opposite with captive wild animals. We breed them for genetic diversity in an attempt to freeze their evolution and preserve this moment in their biology. This is an impossible task.

There are currently more tigers living in captivity than known to be living in ‘the wild’. This seems to indicate that soon ‘wild’ animals will more closely resemble domestic animals in terms of their reliance on humans and our control over their future. Therefore as conservation and domestication begin to blur we will need to recalibrate our understanding of what wildness is and what it means for humans to live in a world with less of it. Redesigning institutions of captivity, such as zoos, can help us to accept our impact on wildlife, but also to question and consider how we would like to interact with wild animals and if they are an important part of our lives and imagination.

TLP: How important is feasibility? What would you think if any of your designs became reality?

KF: This particular project is quite speculative and imaginative, but the basis for that speculation has to do with real science. I became very interested in the field of biological morphology – an area of biology dealing with the form and structure of organisms, their specific structural features, and how they have evolved over time. Studying morphology brings multiple aspects of animal design into consideration – it requires an understanding of the correlation between environment, genetics, behaviour and physical development. While my designs are probably not feasible for a number of reasons, the potential we now have to shape our future experience of animals is something we must begin to consider alongside what we can engineer them to provide us with physically. Therefore I hope that this type of informed speculation can help prompt people to ask questions about what we need and want from science.