Choosing to draw: philosophy and aesthetics

Whatever else the Romans may have done for us, teaching us to draw was not one of their gifts. The two great works of classical scholarship on animals were Aristotle’s History of Animals, and Pliny the Elder’s Naturalis historia. Neither Pliny nor his Greek predecessor included any illustrations in their natural histories. Everything was done by words.

Instead, animals began to appear in medieval works of art. In glass, they were biblical symbols: the Lamb of God; or the lion, ox and eagle that represent three of the evangelists. Manuscripts, too, contained such pious beasts, but often also more vivacious animals: monkeys capering around the edges of the text, or snails creeping through its borders. Books devoted to animals, bestiaries, were a combination of piety and entertainment. The behaviours of animals gave moral lessons to readers; the hoopoe, for example, was renowned for caring for its parents, licking the mist from their eyes in fulfilment of the fifth commandment. The illustrated animal was above all an emblem, the representation of some divine or virtuous quality.

Albrecht Dürer (1471–1528) was the earliest Northern European to theorise drawing. Taking his cue from the Roman architect Vitruvius, he tried to give ideal proportions for rendering the human body in pictorial form, but found he could not. Forced to conclude that beauty was substantially in the eye of the beholder, he instead advised his readers simply to draw what they saw: ‘For truly: art is rooted in nature, if you can draw it out then it will be yours.’

Emerging from a Renaissance set of questions about the human form and portraiture, Dürer’s drawings set a benchmark for the emergent Northern European standard of art that was made (to use the Dutch term) naer het leven, or ‘from the life’.

The Dutch Golden Age, which produced the aesthetics of life-drawing, was economically founded on voyages around the globe, and we might expect the aesthetics and the economics to share some deep roots. Moreover, as various historians are beginning to show, the rhetorical force of truth-to-life did not at all wipe out emblematic concerns with animals. A lifelike drawing could still contain moral or anecdotal qualities. Thus it was for the ill-fated dodos famously drawn by Savery naer het leven. Savery’s dodos were the ‘gluttons in the dark corners of his paintings, concerned with the bodily and the base’.

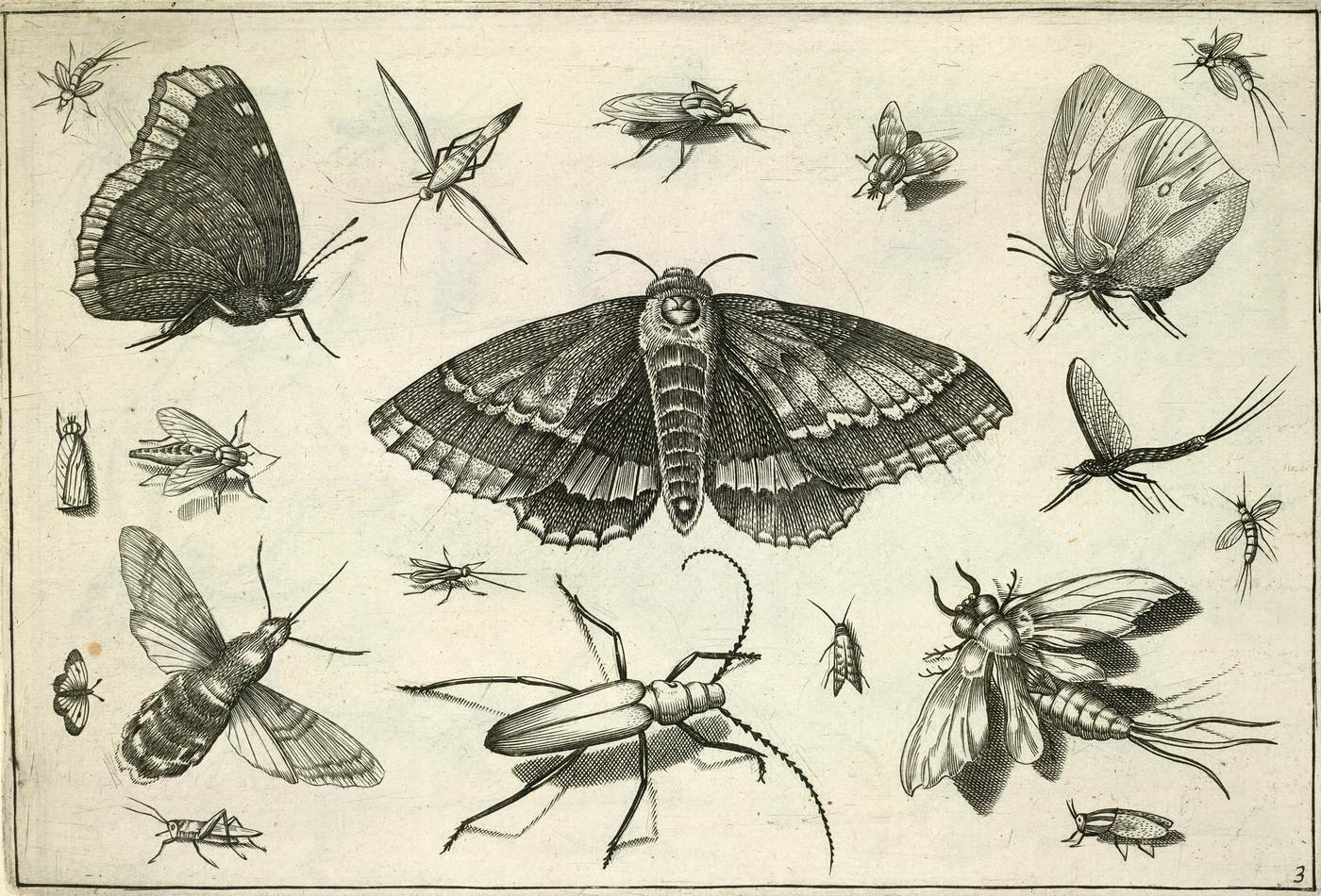

Conrad Gessner’s four-volume Historiae animalium (‘History of the Animals’, 1551–8) and its posthumous addendum on snakes (1587) was the first really substantial animal book to combine Christianised scholarship with the bestiary’s focus on animals. As ever, Pliny and sundry folklore were the sources for Gessner’s tales of animal vices, virtues, and recipes. Horses rubbed shoulders with unicorns, turkeys with griffins. Gessner’s was a menagerie not just of animals, but of juxtaposed pieces of writing about them. Philology – the ancient roots of animal names – was in some ways the most important part of his account. Indeed, the volume was classed by its publisher under ‘grammar and rhetoric’.

Though Gessner’s written facts were not new, his pictures were. In his preface, he boldly claimed that looking at pictures was, in fact, preferable to looking at real animals. Gessner himself proclaimed that his images were ad vivum, whether drawn by himself or by his friends, but what he meant by this statement was complicated; the historian Sachiko Kusukawa concludes that it indicated the production of a reaction in the viewer identical to that produced by the original creature.

One might think that the injunction to draw true to life would sew up the list of requirements for natural-historical artists after its establishment, but that this was not the case. What part of an animal should be drawn? The inside or the outside? What age of animal should be shown? What stage of the life cycle? Should a perfect or imperfect specimen be chosen? Or should a generalised version be created? These different notions of objectivity have been painstakingly traced by historians, showing how idealised, perfected, corrected, typical, averaged, or characteristic forms have at various times satisfied formal desiderata.

Some natural historians looked within their specimens to try and find the thing that should be pictured. In Italy the Lincei, or Academy of Lynxes (founded 1603) – whose members included Galileo Galilei – did exactly this. The name of the society referred to the sharp sight commonly attributed to lynxes, and its members praised pictures as a means of representing, and holding open to scrutiny, the visual properties of nature.

In Restoration England, Robert Hooke (1635–1703) produced the most celebrated animal drawings made using a microscope. His treatise Micrographia (1665) is most famous for its gigantic, hunched flea, though a louse grasping a human hair runs it pretty close. Micrographia is naturally well known for its encomium of technically enhanced visualisation; Hooke regarded lenses as correcting the imperfections of the human senses.

Making drawings: techniques and reproduction

In the eighteenth century, books began to appear that were only or primarily available in coloured form, as opposed to featuring colouration as an optional extra. Maria Sybilla Merian’s Metamorphosis insectorum Surinamensium (‘Transformations of the Insects of Surinam’, 1705) was perhaps the earliest masterpiece of coloured natural history. It showed insects in lifelike colouring, in the company of plants from their surroundings. In some of her works, Merian experimented with trompe l’oeil, painting specimens on backgrounds that themselves curled out from the page or canvas. Thus she drew attention to the cleverness of her execution, to the paradox that the more realistic something appeared, the more artful it actually was. In this sense, Merian alluded to the function of pictures in networks of European savants and collectors, traded and exchanged as stand-ins for nature. Perhaps her use of trompe l’oeil can be regarded as a gentle reproof to this trade, with its effacement of the role of the (sometimes female) painter. Merian travelled to Surinam without a male companion, taking her daughter with her: an extraordinary achievement for the day.

Pictures of animals, once objects of individual exchange, were now part of a highly monetised system of trade. Watercolours had been unique commodities, for wealthy individuals to enjoy or to give as gifts. By the eighteenth century the medium had changed, from watercolour (in the main) to multi-copy coloured engravings – although until they were bound into books, engravings remained items for potential individual trade and collection. The medium of an animal picture determined its use, its pathways between collectors, its fate.

Dying to draw

In Helen Macdonald’s bestselling 2014 memoir, ‘H is’, as her title runs, ‘for hawk’. It is a childlike designation that has mostly gone unremarked: a cosy title that belies the book’s emotionally demanding contents. H is for Hawk is, in fact, a book about the author’s grief and depression following the death of her father, and her recovery through her adoption and training of a goshawk. H is also for Helen. Despite its superficial unlikeliness, there is a certain psychological logic to the book’s title, for the collection of animals is on one level a response to death. By killing something one pre-empts and thus manages the grief of death coming unannounced and accidentally – whether that feared death should befall the animal itself, or – by substitution – some other beloved object. How else to make sense of the passionate love that underpins the wildlife-watching of Victorian hunters, climaxing in the death of the animal?

As a young man, the controversial ornithologist Richard Meinertzhagen (1878– 1967) was attached to the 3rd (East African) Battalion of the King’s African Rifles, in which capacity he was posted to Kenya in the very earliest years of the twentieth century. His diaries are clotted with death, both animal and human. On one level, there is visible sentiment. Many of his entries report genuine distress at the brutality of colonisation, including the revenge killings he himself was ‘compelled’ to carry out – of entire villages, women and all. Moreover, he reports a great fondness for his pet tortoiseshell cat and dog, Baby, both with him in the field, and risks his life to save a monkey that is being tortured by some sailors. Yet at other times Meinertzhagen succeeds in drawing down the blinds of objectivity, for example writing on 20 May 1902:

I was out again today and soon came across a herd of Thomson’s gazelle … After running about a quarter of a mile I managed to get close to [one] … and killed him. I came across a large number of human skeletons this afternoon … I brought home two or three good specimens.

Historians of science in the nineteenth century have identified the birth of the ideal of ‘objectivity’ in this period, portraying it in ways that resonate with Meinertzhagen’s experience. They describe how the production of a ‘view-from-nowhere’ or ‘God’s eye view’ entailed a dramatic disciplining of the emotional, subjective self. In order to present a trustworthy account of nature ‘as it really is’, scientists and authors had to persuade their peers and readers that their own human sentiment and partiality had been well and truly crushed – put out of the picture. Nowhere is this more obviously true than in the field of natural history.

Encounters with animal life became bloodier and bloodier as the nineteenth century unfolded. ‘Collecting the set’ had its darker side, most particularly in colonial history. Hunting, long a necessary means of subsistence for the many and sport for the few, became fatally linked to the projects of science and empire in the nineteenth century. Its primary practitioners were soldiers. In many ways they were the perfect collectors: they had the physical strength necessary for fieldwork and the field skills of tracking; they had the authority to command both European and African persons to act as their support staff. They had the military discipline to catalogue, precisely, where specimens had been shot – to the extent that their data is used by ecologists today to track the movement of species’ populations. And finally, they had networks through which they could prepare and return specimens back to their own countries of origin.

The conquests of Asia and Africa provided the mise en scène for the elaboration of a code of masculinity conspicuously demonstrated by the shooting of animals. Besides displaying a particular construction of gender, the hunting cult also represented an assumption of previously aristocratic rights by the middle classes. Where once the killing of deer was restricted to persons of noble birth, now distant continents provided the opportunity for middle-class men to do the same; if they could not rule at home, they could rule abroad. Besides providing a code and a rationale for colonialisation, hunting also directly subsidised it and made it profitable, through the trade in animal trophies.

In the late nineteenth century US, sporting – that is, hunting – images were particularly successful. The North American landscape was being redesigned for tourists mimicking the activities glorified in such pictures, with the creation of national parks. The earliest users of these reserves tended to enjoy both kinds of shooting (cameras and guns) interchangeably – Theodore Roosevelt being perhaps the most famous, and promiscuous, shooter of the early twentieth century. Fashions, however, slowly changed. US and European zoos grew in popularity, and were re-angled towards juvenile visitors. Family films and television programmes, based around such zoos as well as wild animals, blossomed. All this made game hunting an increasingly distasteful prospect for the average person. Instead, in Africa, conservation reserves were carved out of the game reserves created and policed for the invading colonial elites. By the 1930s, these wildlife preserves were being used for the purpose of allowing tourists to shoot animals with their cameras, creating photographic collections. Pictures such as appeared in the magazine National Geographic were far preferable for the average reader, unable to afford such trips for him or herself.

Even modes of collection that do not depend on direct killing have something of Meinertzhagen’s emotional logic about them. Alphabetical filing, scientific taxonomy, or even drawing all remove the animal cognitively from the materiality of real encounter. These actions kill off the animal’s agency, its noise, its smell: its insistently animal nature. The creature is transmogrified into specimen, into picture, into representative of a taxon. It lives on eternally as memory or as data. Hence the curious sense that the birth of one panda in a zoo is a great cause for celebration – more so than a well-established and secure breeding community in the wild would be. It seems to us that so long as there is one (or, we must concede biologically, a pair), the species is safe, enclosed in our collections. To create a specimen, something must have died. That this sequence of events should be a positive thing is the myth of Noah.

This is an edited extract from The Paper Zoo: 500 Years of Animals in Art, by Charlotte Sleigh, British Library, £25

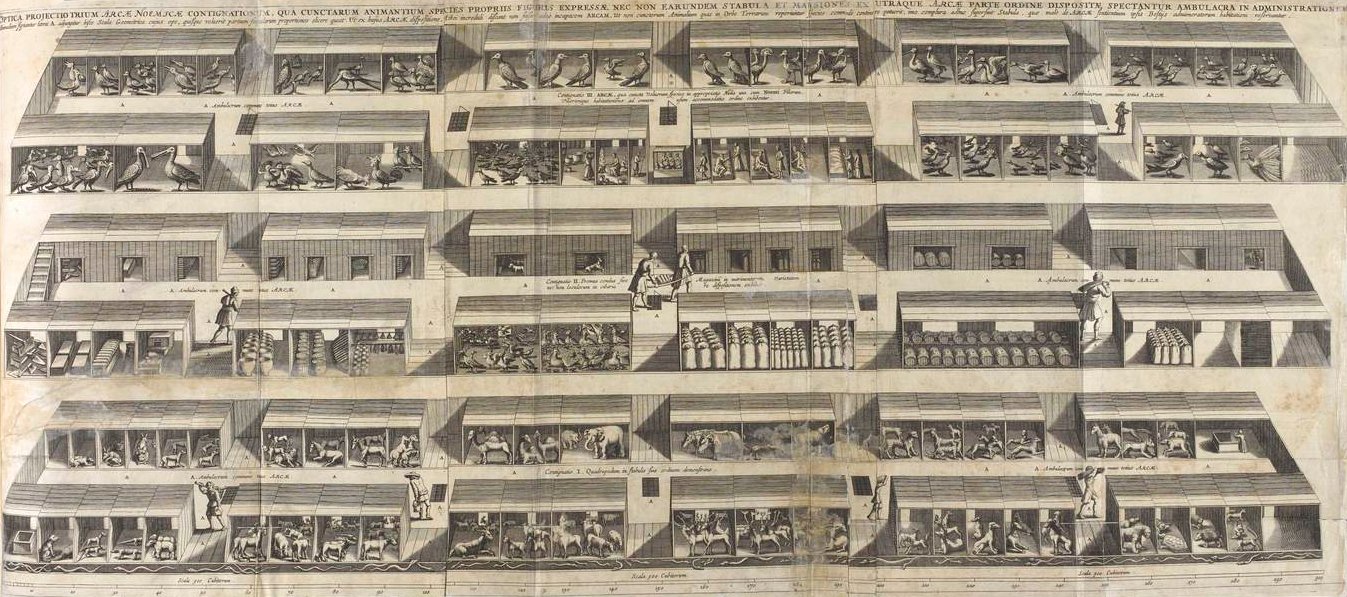

Top image: The three decks of Noah’s Ark. Athanasius Kircher, Arca Noë, Amsterdam, 1675. @The British Library Board.